Non-Timber Forest Products as Drivers of Sustainable Livelihoods and Biodiversity Conservation: A Case Study from the Gond and Baiga Tribal Communities of Central India

26.11.2025

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

Integrated Development Organisation

OTHER CONTRIBUTING ORGANIZATIONS

Indian Institute of Forest Management

DATE OF SUBMISSION

08/2025

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

India

KEYWORDS

NTFP, Tribes, Traditional Knowledge, Baiga livelihood

AUTHORS

Ajoy K Bhattacharya, Ph D, IFS (R)

Chairman, Integrated Development Organization,

Former MD & Country Head, Green Highways Mission, Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, India

Former Founder CEO, Madhya Pradesh Ecotourism Development Board, Bhopal, India

Anjali, MBA(Sustainability)

Indian Institute of Forest Management, Bhopal Madhya Pradesh

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Abstract:

Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) play a critical role in supporting the livelihoods of forest-dependent communities while also incentivizing the conservation of biodiversity. This case study examines the Gond and Baiga indigenous communities of Balaghat District in Central India, exploring how NTFPs contribute to sustainable livelihoods and conservation outcomes. We conducted household surveys (n=168) across ten villages (including Baherakhar) and carried out focus group discussions to assess traditional knowledge, utilization of NTFPs, income contributions, and challenges in NTFP-based enterprises. The results indicate that while NTFPs historically provided significant income and food security – with some studies reporting NTFPs contributing up to 50% of household income for one-third of rural households[1] – their current usage and benefits in the study area are declining due to factors such as restricted forest access, erosion of indigenous knowledge, and market barriers. Only 18% of surveyed households regularly consume NTFP-based foods, despite proximity to forests, as most collectors now treat NTFPs purely as cash crops. Traditional ecological knowledge is fading: about 55% of respondents retain some NTFP knowledge, but 45% have little or none, due to reduced inter-generational transfer and external influences. Key NTFPs in the area (e.g. Mahua, Chironji, medicinal herbs) still contribute to household needs and seasonal income, and they provide vital ecosystem services (food for wildlife, pollination, soil enrichment). However, community members face major hurdles in NTFP commercialization, including poor market access, low prices, post-harvest losses, quality control issues, and insufficient institutional support. This study highlights that strengthening NTFP-based livelihoods through supportive policies – such as Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for forest produce, community-based value addition centers (e.g. Van Dhan Kendras), and inclusive forest co-management – can simultaneously improve rural incomes and incentivize the conservation of forests and biodiversity. We discuss policy implications to bolster sustainable NTFP enterprises (marketing infrastructure, financial and technical assistance, and knowledge revival programs) and suggest that integrating traditional knowledge with modern value chains is crucial. By recognizing NTFPs as “lifelines” for forest communities and ecosystems, development strategies can better align with both poverty alleviation and conservation goals.

Keywords:

Non-timber forest products; Sustainable livelihoods; Indigenous communities; Baiga; Gond; Biodiversity conservation; Traditional knowledge; Central India; Forest policy; Value addition.

Introduction

Forests provide a wide range of goods and ecosystem services crucial to human well-being and environmental health. Beyond timber, forests are sources of food, medicine, fuel, fodder, and other non-timber forest products that millions of people depend upon for subsistence and income [2][3]. Globally, the value of ecosystem services from forests has been estimated at nearly USD 5 trillion annually [4], reflecting their immense contribution to the world’s economy and to the achievement of sustainable development objectives (Costanza et al., 1997) [4][5]. Indeed, the importance of forests for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has been increasingly recognized [6][7]. Forests contribute to SDG1 (no poverty) and SDG2 (zero hunger) by providing food and income to over a billion people worldwide [8][3]. They support health and well-being (SDG3) through medicinal plants, offer affordable clean energy for cooking (SDG7), and play a critical role in climate change mitigation (SDG13) by sequestering carbon [9][10]. Forest resources, when managed sustainably, also underpin SDG8 (decent work and economic growth) via the forest sector’s contribution to livelihoods and SDG15 (life on land) by conserving terrestrial ecosystems [10].

Within the broad spectrum of forest provisioning services, non-timber forest products (NTFPs) hold special significance for rural and indigenous communities. NTFPs are generally defined as biological materials other than timber extracted from natural, modified, or managed forest landscapes – including wild fruits and nuts, vegetables, medicinal herbs, spices, resins, gums, fibers, leaves, honey, mushrooms, and so forth [11]. They can be consumed directly by households or sold in markets, and often have cultural and religious importance in addition to economic value[12]. Globally and in India, NTFPs function as a critical livelihood safety net: it is estimated that about 275 million rural people in India depend on NTFPs for at least part of their subsistence and cash income (Chao, 2012) [13][3]. These products provide multiple livelihood pathways – food security through direct consumption, supplemental income through sale, a buffer against agricultural shortfalls, and even savings on household expenditures when forest products substitute for purchased goods [14][15]. For marginalized forest-dwelling groups, NTFPs often represent “products of last resort” during times of crop failure or economic hardship, thereby building resilience against shocks[15][16]. At the same time, many NTFPs are integral to cultural identity and practices, used in traditional medicine, rituals, and as symbols of heritage.

Nowhere are these dynamics more evident than among the indigenous communities of Central India, such as the Baiga and Gond tribes of Madhya Pradesh. The Baiga are recognized as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG) with a semi-nomadic history of shifting cultivation and profound forest knowledge [17][18]. The very name “Baiga” is locally said to mean “sorcerer-medicine man,” reflecting their reputation for herbal healing knowledge [19][20]. Traditionally, Baigas practiced bewar (slash-and-burn cultivation) and adhered to a belief of minimal interference with the earth – famously refraining from ploughing land on the principle that scratching the breast of “Mother Earth” is a sin [17][21]. Instead, they subsisted on forest produce and shifting patches of cultivation, developing extensive knowledge of wild edible and medicinal plants. The Gonds, a larger Adivasi community in the region, are also intimately connected to the forest environment. They hold cultural traditions such as worship of the Sajha (Indian Laurel) tree and celebration of harvest festivals like Pola to honor their cattle and agricultural cycles [22][23]. Both Gond and Baiga communities have historically depended on forest produce – mahua flowers, tendu leaves, fruits, tubers, seeds and medicinal plants – for their livelihoods, food, health remedies and sacred practices.

However, these indigenous systems face contemporary challenges. Over recent decades, forces of modernization, deforestation, and restrictive forest policies have disrupted traditional livelihood patterns. Many Baiga and Gond families have been resettled out of core forest areas (e.g., around Kanha Tiger Reserve), limiting their access to wild resources [24][25]. Younger generations receive formal education but often at the cost of losing traditional ecological knowledge, and are drawn to wage labor or urban jobs over forest-based work [26][25]. A trend of knowledge erosion is evident – elders report that vital skills in wild food gathering, herbal medicine, and sustainable harvest techniques are not being adequately transmitted to the youth [26][27]. Government policies, while aiming to conserve forests, have sometimes unintentionally marginalized forest dwellers; for example, strict wildlife protection rules and expanded protected areas (such as Kanha National Park and its buffer zone) have curtailed community access to NTFPs, even for subsistence, under threat of penalties [28][25]. Such restrictions, combined with demographic and cultural shifts, risk severing the symbiotic relationship between these communities and their forests.

Research gap: The existing literature on NTFPs in India underscores their aggregate importance – several nationwide studies and reviews have quantified NTFP economic values and highlighted policy gaps (e.g., Tripathi & Kumar, 2016; Gopinath Reddy et al., 2008) [29][30]. Region-specific studies in Central India have documented the rich traditional knowledge of the Baiga (Chauhan & Uniyal, 2019) [31] and the contributions of NTFPs to Baiga livelihoods (Mishra et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2018) [32][33]. Yet, there is a need for integrated case studies that simultaneously evaluate the livelihood role of NTFPs, the status of traditional knowledge, and the linkages to biodiversity conservation in a contemporary context. This research attempts to fill that gap by focusing on a micro-level analysis in a cluster of villages where Baiga and Gond people live adjacent to forests. We aim to assess how much NTFPs currently contribute to household livelihoods (income, food, etc.), how community members perceive and use these forest resources today, and how the use of NTFPs might incentivize or align with conservation of the local forest ecosystem. We also examine the challenges faced in sustaining NTFP-based livelihoods, given the market and policy environment.

Objectives: The study’s specific objectives are: (1) To document the types of NTFPs utilized by the Gond and Baiga communities and their traditional uses and conservation status; (2) To quantify the contribution of NTFPs to household economies and diets, and evaluate the level of dependence on these products; (3) To assess the status of indigenous knowledge related to NTFPs among different age groups; (4) To identify key barriers in the commercialization or enhanced use of NTFPs as a sustainable livelihood strategy; and (5) To discuss policy implications for strengthening NTFP-based livelihoods in ways that also support forest conservation. Ultimately, the study seeks to demonstrate that NTFPs, if supported by enabling institutions, can act as drivers of both sustainable development (improved tribal livelihoods) and biodiversity conservation (through the continued presence and care of valuable plant species in the landscape).

Literature Review

Existing research provides a foundational understanding of the role of NTFPs in sustainable livelihoods and conservation, both globally and in the Indian context. Global perspectives: A systematic review by Aguayo et al. (2023) examined how the forest sector addresses the SDGs, finding that community-based forest management (including NTFP enterprises) often yields co-benefits for poverty reduction and ecosystem protection [34][35]. Case studies from around the world show that NTFPs can contribute significantly to rural incomes, especially for marginalized groups living in or near forests (Derebe & Alemu, 2023) [36]. For instance, in parts of Africa and Southeast Asia, products like honey, rattan, bushmeat, and medicinal plants constitute a substantial portion of household cash flow, often serving as a fallback during agricultural lean seasons (FAO, 2020) [37][38]. At the same time, unsustainable harvesting of NTFPs can threaten those species; hence, balancing use with regeneration is a recurring theme (de Jong et al., 2018) [39]. Gurung et al. (2021) specifically noted that climate change is impacting availability of certain NTFPs in mountain ecosystems, altering traditional harvesting patterns [40][41]. These studies collectively suggest that while NTFPs present opportunities for sustainable development, they require supportive governance and adaptive management to ensure ecological sustainability.

India and South Asia: In the Indian context, NTFPs have been studied extensively due to their importance for tribal communities. It is estimated that NTFPs account for about 20–40% of the annual income of forest-dependent households in India, on average, and contribute ~₹ 200 billion to the national economy [30][42]. Chao (2012) reported that India has one of the largest populations of forest-dependent people globally, with about 100 million forest dwellers and 275 million rural poor relying on NTFPs and other forest resources [43][13]. Some landmark assessments (e.g., the report Forest Peoples: Numbers across the World) highlighted that India’s forest communities utilize a vast range of products, from tendu leaves for local cigarette (beedi) rolling to sal seeds, gums, and tamarind which feed into larger industries [43][44]. A review by Tripathi & Kumar (2016) noted challenges in the NTFP sector such as lack of organized markets, value-addition bottlenecks, and unclear land/tree tenure for collectors [29][45]. Nevertheless, they argue that NTFPs, if coupled with scientific management and fair trade, can significantly contribute to sustainable livelihoods (Pandey, Tripathi & Kumar, 2016) [29][46].

NTFPs in Central India and among Baiga/Gond communities: Central India’s forests (in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, etc.) are rich in NTFPs like Mahua (Madhuca longifolia flowers and seeds), Tendu (Diospyros melanoxylon leaves), Chironji (Buchanania lanzan nuts), Amla (Phyllanthus emblica fruit), gums (from Salai or Karaya), bamboo, and a diversity of medicinal plants. Many of these are economically valuable and also culturally salient for tribes. Baghel & Patil (2022) documented traditional knowledge of the Baiga in a nearby region (Achanakmar Biosphere Reserve, bordering Madhya Pradesh), showing that Baiga healers could identify dozens of medicinal herbs and their uses[47][48]. Similarly, a study in Balaghat District by Mishra et al. (2021) found that NTFPs contributed to both income and nutrition of Baiga households, particularly through sale of tendu leaves (for which the government provides a price) and consumption of wild fruits and tubers during food-scarce months [32][49]. However, they also noted that earnings from NTFPs were declining over time, partly due to resource depletion and partly due to middlemen exploitation in markets. Singh et al. (2020a) carried out an economic assessment of NTFPs among Baiga communities in central India and observed that while older members of the community engaged heavily in NTFP collection, youth were less interested, correlating with a decline in transmission of traditional practices [50][45]. This generational shift is a critical point: traditional knowledge that guided sustainable harvesting (like how much bark to strip, or which season to collect honey to avoid harming bee colonies) is at risk of being lost, potentially leading to unsustainable use or abandonment of valuable resources.

Another relevant aspect in literature is the link between NTFP use and conservation incentives. The logic often cited is that if local communities derive substantial benefits from forest products, they have a stake in protecting the resource base (Gadgil et al., 1993, as cited in various studies). For example, the collection of lac resin (from insects cultivated on host trees like Palas and Kusum) in Central India has traditionally encouraged villagers to preserve those host trees in their vicinity [51][52]. A Down to Earth article by Sinha (2013) recounts how promoting lac cultivation revived interest in planting and conserving native trees, as people saw economic return from them [53][54]. Likewise, efforts to organize Self-Help Groups for processing mahua flowers into beverages or food supplements have shown some success in Madhya Pradesh and neighboring states, simultaneously valorizing the Mahua tree in local landscapes (Kacker, 2022) [55][56]. These experiences support the hypothesis that sustainable use of NTFPs can be aligned with conservation – a paradigm embedded in programs like India’s Joint Forest Management and the more recent “Van Dhan Yojana” (a scheme launched in 2018 to enhance tribal incomes through NTFP value addition). Early evaluations of the Van Dhan Vikas Kendras (tribal forest product centers) indicate improved incomes for participants, though coverage remains limited and challenges like marketing persist [57][58].

In summary, prior studies set the stage by highlighting: (a) NTFPs’ multifaceted role in sustaining forest communities economically and culturally; (b) the threats to these systems from external pressures and internal changes; and (c) the potential for synergy between livelihood enhancement and forest conservation via NTFPs, if the proper support mechanisms are in place. Building on this foundation, our case study focuses on the Gond and Baiga communities in a specific locale (Baherakhar and surrounding villages) to provide an updated, fine-grained analysis. It contextualizes the broader trends within the local reality of Central India in 2023, incorporating community voices regarding both the promise and problems of relying on forest products in the current era.

Methodology

Study Area: The research was conducted in Balaghat District of southeastern Madhya Pradesh, India, with a focus on Baherakhar village and nine other surrounding villages in Baihar and Birsa blocks (Bhimlat cluster). Balaghat district is characterized by undulating forested highlands of the Satpura range and lies just north of the Maikal Hills and Kanha Tiger Reserve. The district has about 52% of its geographic area under forest cover [59][60], comprising dry deciduous forests dominated by species like Sal (Shorea robusta), Teak (Tectona grandis), Mahua (Madhuca longifolia), Terminalia species, bamboos, and others. Administratively, Balaghat is one of the 55 districts in Madhya Pradesh, and is considered economically underdeveloped – it was identified among India’s 250 most backward districts, qualifying for special development grants [61][62]. The selected study villages, including Baherakhar, lie in the Bhimlat Gram Panchayat in Baihar Tehsil, adjacent to forest areas that form part of the Kanha reserve’s periphery. Baherakhar is geographically located at approximately 22.12° N latitude, 80.72° E longitude [63][64], at an altitude ranging ~486–554 m above sea level in gently hilly terrain [65][66]. It is a small tribal village of about 3 km² area [67][68], with a population primarily of Baiga and some Gond families. The village is accessible by a rural road and is ~10 km from the nearest town (Malajkhand) [69]. Table 1 presents a land-use summary for Baherakhar (based on revenue records and 2011 census data), and Table 2 provides key profile details of the village.

Table 1. Land use of Baherakhar Village (Census 2011). The village’s total geographic area is 303.6 hectares, of which about 13.6% is forest. Over 60% of the land is under cultivation (rainfed agriculture), with no irrigated area. Non-agricultural uses (habitation, roads, etc.) cover ~2.7%, and ~9.8% is culturable wasteland with potential for cultivation[70][71]. Notably, there is no permanently barren land, and fallow lands constitute about 13% of the area (including ~8.8% current fallows), indicating land left fallow for soil recovery[72][71].

| Land Use Category | Area (ha) |

| Total geographic area | 303.6 |

| Forest area | 41.4 |

| Non-agricultural uses (settlements, roads, etc.) | 8.2 |

| Barren & uncultivable land | 0.0 |

| Permanent pastures & grazing land | 1.8 |

| Miscellaneous tree crops (orchards) | 0.0 |

| Culturable waste land (currently uncultivated) | 29.8 |

| Fallows other than current fallows | 13.0 |

| Current fallows (this season uncultivated) | 26.7 |

| Net area sown (current cultivated land) | 182.8 |

| Total unirrigated land | 182.8 |

| Area irrigated by any source | 0 |

Source: Compiled from village land records (Census of India, 2011) [73]. Over 13.6% of the village land is forested, while 60.2% is net sown area, reflecting heavy reliance on rainfed farming. The absence of irrigated land underscores that agriculture is entirely rainfed in Baherakhar [73].

Table 2. Baherakhar Village Profile – Key geographic and administrative information [74][75].

| Particular | Value |

| Village Name | Baherakhar[74] |

| District, State | Balaghat, Madhya Pradesh (India) |

| Latitude, Longitude | 22.1198° N, 80.7187° E [63] |

| Gram Panchayat (local council) | Bhimlat [76] |

| Nearest town (distance) | Malajkhand (≈10 km) [69] |

| Distance from all-weather main road | 0 km (located adjacent to a road) [69] |

| Gram Panchayat representatives | 12 members (6 female) [77][78] |

| Village Sarpanch (elected head) | Mr. Parbat Meravi [79] |

| Total area of village lands | 3.03 km² [67] |

| Area of entire GP (Bhimlat) | 7.47 km² [80] |

| Neighboring villages in Panchayat | Bhimlat, Basinkhar, Sarasdol, Samnapur [81] |

Note: Baherakhar is one of several Baiga- and Gond-inhabited villages in this cluster, lying near the buffer of Kanha Tiger Reserve, which indicates proximity to rich forest biodiversity [82].

Within these communities, livelihoods are a mix of subsistence agriculture, wage labor, and forest gathering. Agriculture is largely rainfed mono-cropping (rice, maize, some pulses), with low productivity. NTFPs traditionally filled crucial gaps – providing food during the lean months and cash income from sale of products like mahua flower, mahua seed (for oil), tendu leaves (for beedi rolling), and others during their season. However, as noted, access to forest resources is partially regulated by the Forest Department, and villagers typically need permits or operate through government-sanctioned collection schemes (e.g., tendu leaves are collected and sold to a government agency at fixed rates).

Sampling and Data Collection: We employed a mixed-methods approach. First, village sampling: Ten villages with significant Baiga and Gond populations were selected purposively within the Balaghat region. The selection criteria ensured that the villages were adjacent to or within forest areas and that NTFP collection was known to be practiced by residents. These included Baherakhar, Bandhatola, Basinkhar, Baigatola, Bhimlat, Balgaon, Baihar (village cluster), Birsa (village cluster), Chirchiranpur, and Samnapur. Within each village, we used simple random sampling of households for the survey. We aimed for roughly 15–20 respondents per village, proportional to size. In total, 168 individuals (male and female household heads or knowledgeable elders) were interviewed across the villages [83][84]. These comprised a mix of Gond and Baiga tribe members (approximately 60% Baiga, 40% Gond in the sample, reflecting the local demographics). We ensured inclusion of various age groups to gauge knowledge retention.

Data was collected primarily through a household questionnaire survey and supplemented by key informant interviews and focus group discussions. The survey questionnaire (see Annex) covered sections on: household demographics and livelihood activities; extent of reliance on NTFPs (for income, food, medicine); types and quantities of NTFPs collected; seasonal availability and usage patterns; traditional knowledge (e.g., ability to identify uses of certain plants); perceptions of changes in availability; and awareness of government schemes related to NTFPs. It also included Likert-scale and multiple-choice questions about challenges in NTFP collection and marketing (to identify perceived barriers). The questionnaire was prepared in English and then administered with the help of a local interpreter in Hindi/tribal dialect as needed [85].

We conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) in two villages (Baherakhar and Bhimlat) with groups of elder Baiga men, Baiga women, and Gond mixed group, to gather qualitative insights on cultural importance of forest products, community history, and changes over time. Participant observation techniques were used during forest walks with villagers to identify key plant species and their uses (an ethnobotanical component).

Data Analysis: Quantitative survey data was coded and analyzed using descriptive statistics. We computed frequencies and percentages for household reliance on NTFPs, proportions of respondents with certain knowledge levels, etc. (e.g., % of households that consume wild foods, % citing particular problems). Where relevant, means and medians were used for continuous data (like income from NTFPs). The sample size (168) allowed for estimating proportions with a reasonable confidence interval for the community. We did not undertake multivariate analysis given the primarily descriptive objectives, but we did cross-tabulate some responses by age group to see generational differences (e.g., younger vs older respondents’ knowledge). The qualitative data from interviews and FGDs was thematically analyzed – notes were reviewed to extract common themes (such as “restricted access” or “lack of market knowledge”) which helped interpret the quantitative findings.

Additionally, we compiled an inventory of important NTFP species mentioned by the community, noting their local names, uses, and referencing their conservation status from secondary sources (IUCN Red List, etc.). This is presented in Table 3 in the results. We also gathered secondary data on Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for certain NTFPs and typical market prices (from government notifications and market surveys) to compare economic values – summarized in Table 4.

Throughout analysis, an effort was made to triangulate information – for instance, if survey respondents reported a decline in mahua yield, we cross-checked with forest department records or literature if available, and with qualitative narratives. We also used mapping (GIS) to provide visual context: an NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) map of the area was generated to illustrate vegetation cover (Figure 1), a location map situating Baherakhar within Balaghat/Madhya Pradesh (Figure 2), and an elevation contour map (Figure 3) to understand terrain influences on land use. These maps were created using satellite data and QGIS, and are included for context.

Ethical considerations: Prior informed consent was obtained from all participants, explaining the study’s academic nature and ensuring anonymity of individual responses. The local community leaders and the Gram Panchayat were consulted and gave permission for the study. Given the cultural sensitivity, special care was taken, particularly when inquiring about traditional knowledge and practices, to show respect and reciprocity (we shared some results and provided a briefing to the village council at the end of the study).

Results

Traditional Knowledge and Cultural Significance of NTFPs

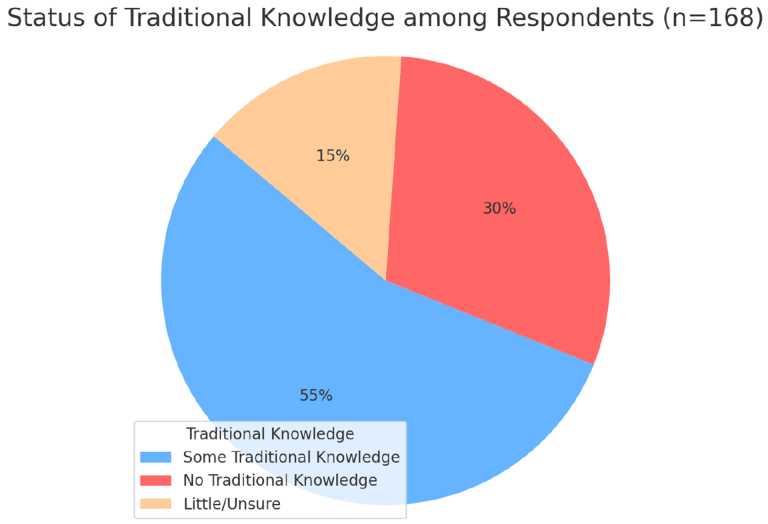

One of the striking findings of the survey is the erosion of traditional ecological knowledge in the community. When asked about their knowledge of forest products (such as identifying medicinal plants or knowing their uses), only about 55% of respondents reported having “some traditional knowledge,” whereas 30% admitted to having no traditional knowledge and ~15% said they had only a little or were unsure (Figure 4).

Figure 4 shows the breakdown of self-assessed traditional knowledge among respondents (n=168). This indicates that a slight majority still retain at least some indigenous knowledge of NTFPs, but a very large minority (45% combined) have experienced knowledge loss or never acquired much in the first place. In group discussions, elders described a rich array of knowledge held by their forefathers – for instance, knowing over 50 edible wild plant species and their seasons, or techniques for extracting specific gums or resins – and lamented that “now even our children do not recognize more than a few fruits in the forest.” The reasons cited for this decline include lack of inter-generational transfer (as younger people spend more time in formal schooling or migrant labor), the influence of modern lifestyles (leading to disinterest in “jungle” foods and medicine), and restricted forest access curtailing the practice that reinforces knowledge[26][24]. Some respondents also mentioned that with fewer elders actively practicing herbal medicine or rituals, the community institutions that preserved knowledge (like the role of the village Gunia or medicine-man) are weakening.

Despite this overall decline, the knowledge that does persist remains significant. Baiga healers (Gunias) in the village could still list many herbal remedies. For example, the root of Shatavari (Asparagus racemosus) is collected to prepare a tonic for women’s reproductive health, and the leaves of Gudmar (Gymnema sylvestre) are known as a treatment for diabetes (chewing them reputedly suppresses the taste of sugar) – reflecting deep indigenous knowledge aligned with Ayurvedic uses[86][87]. The cultural importance of certain NTFPs remains high: Baiga women continue the tradition of tattooing, for which they use natural dyes obtained from forest plants. Festivals like “Jawara” involve collecting specific forest leaves as part of the rituals. The Gond community’s Pola festival involves making sweets from mahua flowers and worshipping the bullocks with garlands that sometimes include forest herbs. These practices demonstrate that NTFPs are not merely economic assets but are woven into cultural and spiritual life. As one elder phrased, “Our forest is our ‘annadata’ (provider of grain) and also our ‘vaidya’ (doctor).”

NTFP Utilization and Dietary Role

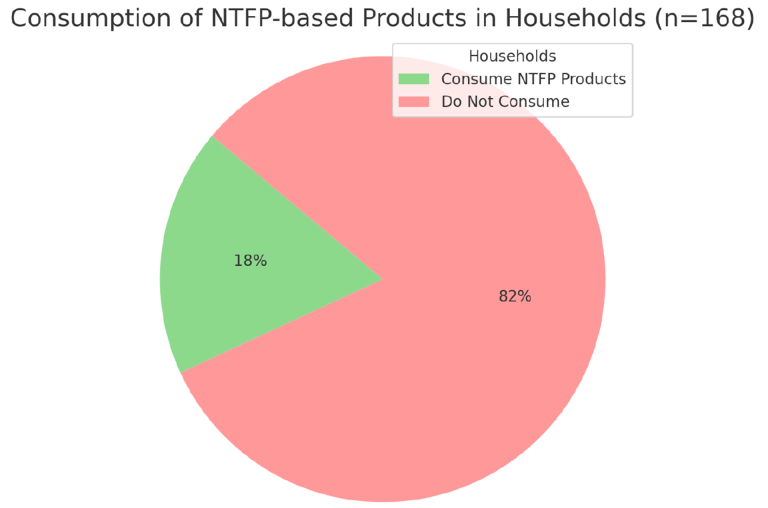

Contrary to what might be expected given the forest proximity, daily consumption of NTFPs or NTFP-derived foods is relatively low among the households. According to the survey, only 18% of households reported regularly consuming NTFPs (in the form of wild fruits, tubers, greens, mushrooms, or products like mahua flour or herbal decoctions). The vast majority, 82%, do not incorporate NTFPs into their regular diet (Figure 5).

This low utilization might seem surprising, but qualitative insights clarify the context. Many families said that while they occasionally eat something like wild mushrooms or bamboo shoots, these are seasonal treats rather than staples. Several NTFP foods are considered “famine foods” – e.g., certain tubers or woody greens are only consumed when cultivated food is scarce. There is also a generational difference: older people recall eating forest foods more often in their childhood, whereas younger respondents largely rely on store-bought staples. Some wild foods have strong or acquired tastes that the younger generation does not enjoy (e.g., the bitter tubers or pungent leafy vegetables from the forest).

Moreover, some NTFPs that are edible are instead sold for cash rather than eaten. For instance, mahua flowers can be dried and ground into a flour for local porridge, but most families prefer to sell the flowers for income (especially since government or traders offer ₹30–40 per kg) and then buy rice/wheat from the market[88][89]. Similar is the case for Chironji nuts – they are a delicacy, but virtually none of the locals consume them because the nuts fetch high prices from traders, so everything collected is sold. In effect, many households “trade-off” direct consumption for cash income which is used to buy other foods.

There are also practical challenges mentioned: many wild foods require significant labor in processing or cooking (e.g., removing bitterness, or cleaning), and given time constraints, people often opt for easier options. One respondent noted, “We like mahua ladoos (sweet balls), but it takes a lot of effort to prepare. It’s easier to sell mahua and buy biscuits from the market.” This indicates a nutritional transition underway – even in these forest fringe villages, store-bought foods (however less nutritious) are replacing traditional forest foods, likely due to convenience and aspiration for modern diet.

Nonetheless, certain NTFPs remain important for nutrition in specific seasons. Mahua flowers are rich in sugars and were historically a crucial source of calories at end of the dry season; some older villagers still ferment mahua to produce a traditional alcoholic drink which they consume moderately for warmth and as a cultural practice. Amla (Indian gooseberry) and Tendu fruits are collected by children for snacking (though not in huge quantities). Wild mushrooms (several varieties) sprout in the early monsoon and are a cherished food when available – villagers say they prefer these mushrooms to any farmed ones because of their flavor. The low overall consumption percentage (18%) thus belies that during certain times of year, a larger share of households might eat specific NTFPs, but on an annualized basis it’s limited.

A major implication of this finding is on nutrition and food security. If local nutritious forest foods (like amla, wild leafy greens, etc.) are underutilized, there might be hidden nutritional deficits especially in minerals and vitamins that these foods provide. Some government programs (e.g., under the Forest Department or Tribal Affairs) are encouraging kitchen gardens and cultivation of medicinal plants to improve dietary diversity, but uptake appears limited so far. The community’s focus has shifted to NTFPs as an income source more than a direct food source.

Economic Contribution of NTFPs to Household Livelihoods

From an income perspective, NTFPs still feature in the livelihood portfolio of many households, but their share of income has declined compared to a generation ago (according to oral histories). Among surveyed households, roughly 40% reported earning at least some cash income from NTFP sales in the past year. However, in most cases it was a small fraction of total income (less than 20%). Only about 10% of households could be considered significantly dependent on NTFP income (deriving over 30% of their annual earnings from it). These tend to be the poorer families with limited agricultural land, for whom forest gathering is a livelihood of last resort.

The main NTFPs contributing to cash income in Baherakhar and surrounding villages are: tendu leaves (collected in May–June for the bidi industry), mahua flowers (April–May, sold for liquor brewing or animal feed), mahua seeds (May–June, for oil extraction), char (Chironji) seeds (April, sold as nuts), tamarind fruit (collected from the forest or homestead trees), lac resin (if cultivated on palas or kusum trees, though this practice has reduced), and wild honey (collected by a few specialist individuals). Of these, tendu leaves and mahua flowers are the most widespread activities. The government has a procurement system for tendu leaves where collectors are paid a standard rate per bundle of leaves; in our study area, this was reported as around ₹150 per 100 bundles (each bundle ~50 leaves). An average collector might gather 300–400 bundles in the season, earning on the order of ₹4,500–6,000 per season. Mahua flower collection yields maybe 50–100 kg per household (depending on tree access), and with MSP around ₹35/kg in recent years[90][88], a household could earn ₹1,750–3,500 from mahua flowers if they sell all. However, local market prices sometimes fall below MSP (e.g. to ₹25/kg in a glut)[91], unless sold to a cooperative that honors MSP or higher[88].

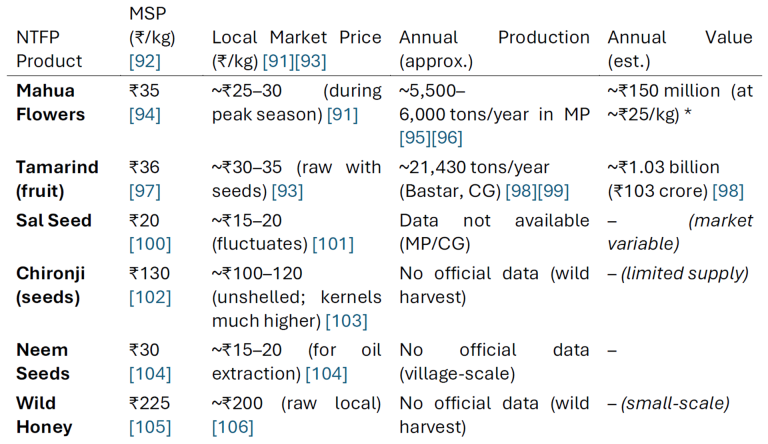

Table 4 provides an illustrative comparison of the government-announced Minimum Support Price (MSP) vs. typical local market prices for some major NTFPs, along with rough estimates of their annual production and value in the region. This contextualizes the economic stakes of these products.

Table 4. Economic Value of Key NTFPs – MSP vs. Market Prices. Data are illustrative for Madhya Pradesh (MP) or neighboring regions, compiled from government reports and literature. “Annual production” is an approximate figure for the state or region, and “Annual value” is a rough estimate of the product’s worth (in INR) at the given price.

Notes: MSP = Minimum Support Price under the Government of India’s scheme for Minor Forest Produce (as of 2018–2020 revisions) [107]. Local market price is what collectors typically receive from middlemen or at weekly tribal haats; these can be lower than MSP if the procurement mechanism is not accessible, or occasionally higher if demand spikes. For example, while MSP for mahua flower was set at ₹35/kg, some tribal cooperatives offered up to ₹40/kg to encourage collection[88], whereas private traders might pay only ₹20–25 if there’s oversupply. The annual production figures give a sense of availability: e.g., Madhya Pradesh produces an estimated 5.5–6 thousand tons of mahua flowers per year[95], reflecting the huge volume of subsistence and trade use. Tamarind is more abundant in neighboring Chhattisgarh (Bastar region ~21k tons/year) [98]. These NTFP economies can be worth tens or hundreds of crores of rupees at the regional scale. However, the actual earnings by the primary collectors are a small fraction of that value, due to long market chains and lack of value addition at source [96][108].

From the household perspective in our study, the average annual income from NTFPs (for those who collected any) was approximately ₹5,000–6,000. This is relatively low – for context, many of these households also work as agricultural or casual laborers earning around ₹200 per day in season, so a single month of labor work could equal the NTFP income of a whole year. There were a few exception cases: one family known for collecting wild honey earned an estimated ₹15,000 in the year from honey sales (they scale tall trees and collect honey from rock bee hives, a risky but lucrative job). A couple of households involved in lac cultivation (in one of the villages) got a decent return when market prices for lac were high in one season (they earned ~₹10,000 from lac in 2021), but then a pest outbreak ruined their crop the next year. Such variability is common – NTFP yields are highly season-dependent and inconsistent.

Critically, the elders contrasted today’s earnings with the past. Many Baiga elders claimed that “20 years ago, a hard-working family could live off the forest”. They narrated that in the past they could barter or sell forest goods for grains and other necessities, estimating that previously NTFPs made up more than half of their livelihood. Our data cannot verify past figures, but secondary sources support a decline: a recent grassroots report in the region noted that an average Baiga family’s annual income from NTFPs has dropped from around ₹20,000–30,000 a couple of decades ago to almost negligible levels today [109]. One reason is that forests have become less yielding – for instance, there are fewer fruiting tendu trees or the mahua trees produce less due to climate factors. Another reason is reduced access and smaller collection areas (because of conservation laws). A journalist piece on the “Heritage Mahua Liquor” initiative in MP reported that despite government efforts to create marketable mahua products, tribal women earned as little as ₹13,000–14,000 in two years from selling mahua liquor, far below expectations [110][111]. This resonates with our findings that current earnings are modest.

Important NTFP Species and Their Uses

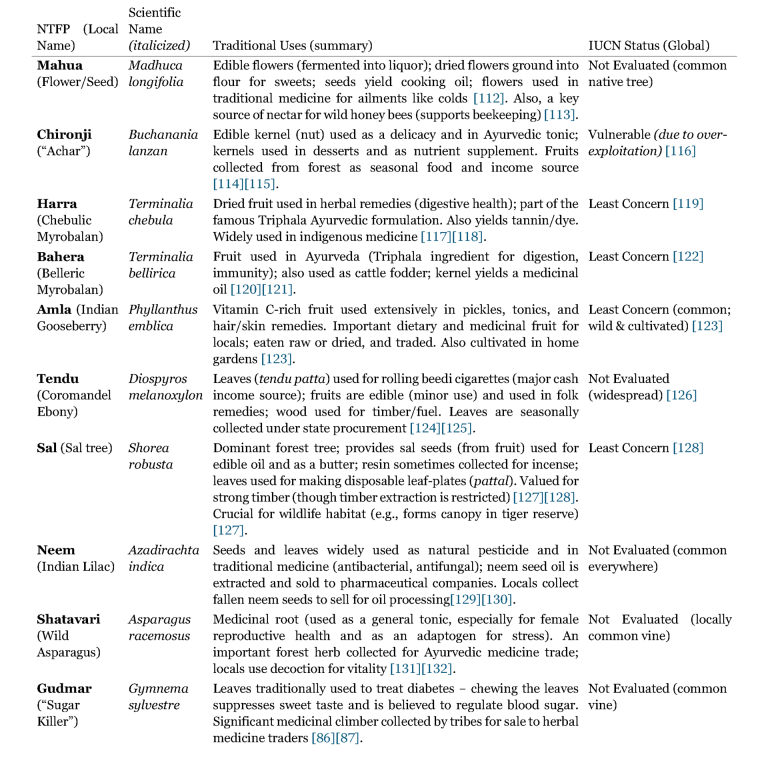

During the study, we compiled information on locally important NTFP species. Table 3 lists a selection of these species, including their local (common) names, scientific names, traditional uses as described by community members, and their conservation status (as per global IUCN Red List where available). This table illustrates the breadth of products and associated knowledge in the area.

Table 3. Important NTFP Species in Baherakhar region – Local Uses and Conservation Status. Uses are summarized from field interviews (indigenous knowledge), and conservation status is from the IUCN Red List global assessment.

Sources: Field survey and ethnobotanical records from the community (2023). Conservation status from IUCN Red List: notably, most species listed are not globally threatened (e.g., Terminalia spp. are Least Concern) [133], but some like Chironji are categorized as Vulnerable due to regional over-harvest [133]. Local abundance vs. threat: Many of these NTFPs are still relatively abundant in our area (thanks to the protected forests), but community members noted signs of pressure – for instance, smaller sizes and lower frequency of Achar (Chironji) trees now, compared to a generation ago, due to unsustainable seed collection and grazing impacts. This underscores the importance of sustainable harvest practices.

The above table indicates the range of benefits that NTFPs provide: nutrition (amla, mahua), health remedies (harra, bahera, neem, gudmar, etc.), cash income (tendu leaves, chironji, sal seeds), and materials for daily use (leaf plates from sal or dona pattals from Shorea robusta leaves, etc.). The conservation status column also highlights an important point: a species can be globally secure yet locally threatened if harvest is not managed. For example, Buchanania lanzan (Chironji) is listed as Vulnerable in its native range due to heavy exploitation for its nuts [114][133]. Our findings support this, as villagers mentioned that they have to go deeper into the forest to find Achar trees nowadays compared to the past. Conversely, species like mahua and tendu are still quite common in the landscape, which bodes well for sustainability if proper care is taken.

Perceived Barriers to NTFP-based Livelihoods

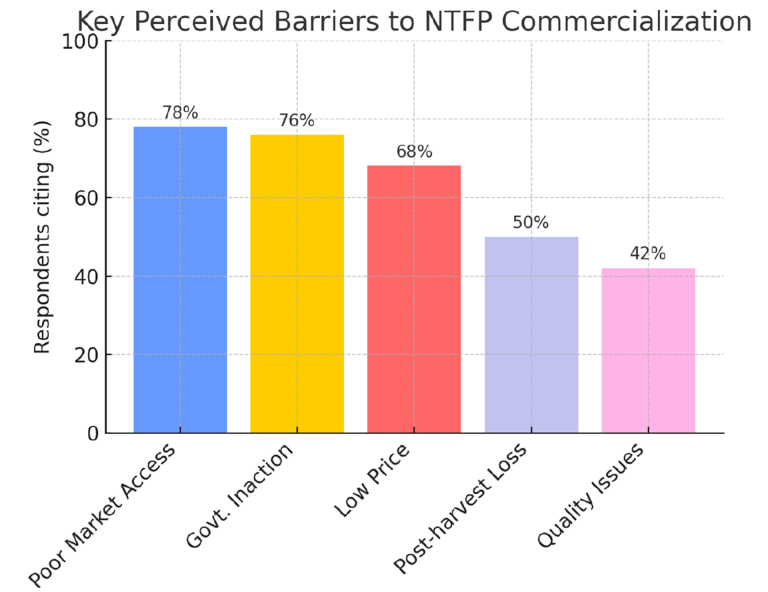

A core part of our investigation was to understand what challenges the community faces in expanding or improving their NTFP-based livelihoods. Through survey questions and discussions, several key barriers were consistently identified. We quantified the frequency of each issue being mentioned by respondents. The results are summarized in Figure 6, which ranks the main barriers by the percentage of respondents who cited them.

The five dominant challenges are:

- Poor market access/conditions – cited by 78% of respondents. This refers to the lack of nearby markets or buyers, and the community’s weak bargaining power. Many villagers rely on a single annual visit by a trader, or have to travel far to sell their produce. They also lack market information on pricing, often resulting in distress sales. For instance, some did not sell mahua last year because the trader offered too low a price, but they had no alternative buyer. Market access issues are compounded by the remote location and poor transport infrastructure (no cold storage or processing facility in the vicinity).

- Government inaction/inefficiency – 76% mentioned. Despite various schemes (like the MSP for MFP, and the Van Dhan Yojana), people feel that on the ground, support is lacking. They pointed to irregularities or delays in government procurement (e.g., payments for tendu leaves sometimes arrive months late). The Forest Department is seen as more focused on restrictions than on helping villagers sustainably use resources. Some also mentioned bureaucratic hurdles in accessing schemes like needing to form cooperatives or SHGs which they find difficult without guidance. Essentially, there is a gap between policy intent and implementation at the grassroots.

- Low prices for NTFPs – 68% cited. Even when they can sell, the price obtained is often disappointingly low, making the effort seem not worthwhile. This low pricing is partly due to middlemen taking a large cut, and partly due to the lack of value addition at source. For example, raw tamarind with seeds sells cheaply, but if they could de-seed and pack it, it would fetch more. Similarly, chironji in unshelled form gets a fraction of the price of the kernel (which is labor-intensive to extract, and they lack tools for it). The community is aware that the end-market prices are higher (they hear that mahua liquor sold in cities is expensive, or herbal medicine companies profit from cheap raw materials collected from them). This price disparity breeds a sense of exploitation.

- Post-harvest losses and lack of processing – ~50% mentioned. NTFPs often require proper drying, cleaning, or storage to preserve quality. Many collectors lack the facilities to do this well. In our observation, mahua flowers left to dry on open ground sometimes get damp or eaten by livestock, leading to spoilage. Some percentage of collected fruits (like amla or tamarind) spoil before they can be sold or consumed, especially in years of glut. Without local processing units (like a small oil expeller for neem seed or mahua seed, or a drying center), the community sells raw produce which fetches less and is more prone to spoilage. They recognize that establishing local processing (like the Van Dhan center concept) could reduce waste and improve income, but they currently lack capital and technical know-how to do so.

- Quality issues – cited by 42%. This ties in with processing; buyers often pay less claiming that the product is of subpar quality – e.g., smoke-tainted honey (since traditional honey extraction involves fire), or foreign matter in dried mahua. Villagers do not have equipment for maintaining high quality (e.g., food-grade containers, etc.). The lack of standardized grading means they take whatever price is offered. Training on better collection and handling techniques was highlighted as a need by some respondents who had heard of it elsewhere.

In addition to these, a few other challenges came up less frequently but worth noting: resource scarcity – some fear that the availability of certain NTFPs is dwindling (like fewer medicinal plants due to over-harvest or forest thinning); legal restrictions – about 15% mentioned fear of forest guards or legal trouble if they take certain products (for example, technical illegality of collecting in core zones); competition and theft – a few noted that when a product is valuable, outsiders sometimes come and collect from their forest patch (e.g., outside traders sending laborers during tendu season). While not a top concern among most, this points to the need for clear community rights and management.

Overall, these barriers explain why, despite the presence of valuable forest resources, the community has not substantially improved their livelihood from NTFPs in recent times. As one respondent succinctly put it, “There is money in the forest, but we are unable to reach it.”

Livelihood Strategies and Recent Trends

Finally, it is important to situate NTFPs within the broader livelihood strategies of these communities. Our study found that nearly all households pursue multiple livelihood activities: small-scale farming, NTFP collection, daily-wage labor (often in government programs like MNREGA, or in nearby towns), and some craft or service. For example, a Baiga family might cultivate 1 hectare of upland rice (mostly for their own consumption), gather mahua and tendu for seasonal cash, and the men might migrate for a couple of months to work in a brick kiln, while the women might weave leaf-plates from sal leaves for a bit of income. This diversification is a hedge against the unreliability of any single source.

A trend observed is increased reliance on wage labor and agriculture, and decreased reliance on forest gathering compared to the past. Some reasons we have covered (knowledge loss, less forest access). In Baherakhar’s case specifically, people mentioned that after being relocated out of some core forest areas in the early 2000s (due to tiger reserve buffer delineation), they had to focus more on farming on allotted land and seek jobs under government schemes. This resettlement has had a mixed impact – on one hand, it reduced the area they could forage in; on the other hand, those who got some land now try to improve farming output. The yield of their traditional agriculture is low, however, prompting interest in supplementary livelihoods like NTFP processing if it can be developed.

One relatively successful initiative in the area has been the formation of a women’s Self-Help Group (SHG) that started making mushroom powder from collected wild mushrooms and cultivated oyster mushrooms. This was aided by a local NGO in 2021. The SHG could sell the powder in nearby towns as an organic product. Though on a small scale, it provided proof that value addition can significantly raise returns (they earned ₹400 per kg for the dried powder, whereas raw mushrooms might effectively fetch <₹100/kg considering weight loss when drying). It also allowed storage and year-round selling, addressing seasonality. Encouraged by this, there have been proposals under a government scheme (SFURTI – a cluster development program – and an LEDP livelihood project) to process mangoes (which are abundant in some villages) into dried mango powder and pickles for year-round sale. While mango is technically an agro-horticultural product rather than wild forest produce, it fits into the broader narrative of adding value to local natural products to improve livelihoods. Such diversification could reduce pressure on purely forest-derived products while still leveraging local biodiversity.

In summary, the results portray a community in transition. NTFPs remain important – culturally as a link to their heritage, and economically as a safety net – but are not currently a primary driver of income for most. The potential for NTFPs to contribute more is evident (the forests contain valuable assets), yet various challenges have kept that potential from being fully realized. The following discussion delves into what these findings mean in a larger context and how strategic interventions could make NTFPs a win-win for both the people and the forests.

Discussion

The case of the Gond and Baiga communities in Baherakhar and surrounding villages exemplifies the complex interplay between traditional lifestyles and modern pressures. Our Page 19 of 30

Integrated Development Organisation – A K Bhattacharya

findings resonate with patterns observed in other forest-dependent communities, while also highlighting unique local specifics. We discuss below the implications for sustainable livelihoods, biodiversity conservation, and the policies needed to bridge the gap between the two.

1. Decline of Traditional Knowledge and its Consequences: The erosion of indigenous knowledge (with 45% of surveyed individuals lacking it) is both a symptom and a cause of reduced reliance on NTFPs. As younger generations lose familiarity with wild foods and medicinal plants, they are less likely to use or manage them, potentially accelerating a feedback loop of disuse and further knowledge loss [26][27]. This matters for sustainability because traditional practices often carried implicit conservation principles – for example, only harvesting certain amounts, or in specific seasons, or leaving some fruits for wildlife. With those norms fading, any exploitation that does occur could become unsustainable. On the other hand, as knowledge wanes, valuable resources may simply be ignored and eventually lost (culturally or even biologically if not conserved). This aligns with concerns raised by other studies (e.g., Pilgrim et al., 2008) that the loss of traditional ecological knowledge can lead to poorer conservation outcomes. In our case, one could argue that because the Baiga revere certain species (like mahua or the saj tree) [22][134], they historically protected them. If those cultural reverences diminish, the incentive to protect those species might too. It’s notable that community members themselves articulated the need to document and preserve traditional knowledge for future generations – suggesting an openness to initiatives like community knowledge registers, school curricula incorporating local knowledge, or elder-youth mentorship programs. Such initiatives could be part of a larger strategy to revitalize interest in NTFPs among youth, framing it not as backwardness but as valuable heritage and potentially a viable livelihood.

2. NTFPs as Safety Nets vs. Growth Engines: Currently, NTFPs function more as a livelihood safety net – an income of last resort, a seasonal supplement – rather than a primary livelihood driver. This is common worldwide; as Neumann & Hirsch (2000) observed, NTFPs often provide breadth (security) but not depth (high income). In our study area, despite rich forests, NTFPs don’t lift households out of poverty but do prevent extreme destitution or hunger (e.g., during drought when crops fail, they can fall back on forest foods). The question for development is whether NTFPs can be transformed into a growth engine for local economies. The low current consumption of NTFPs (only 18% households regularly consuming) also implies that there is room to improve local nutrition by reintroducing forest foods into diets, which would be a direct livelihood (well-being) improvement. Encouraging local consumption of, say, amla (for vitamin C) or certain leafy greens and mushrooms could combat micronutrient deficiencies. The barrier here is partly taste and preference shifts, which could be addressed through awareness (possibly via the health department or NGOs demonstrating recipes that make these foods palatable to younger folks). It’s a subtle point, but one that connects livelihoods with health outcomes.

3. Sustainability and Conservation Implications: The relationship between NTFP use and biodiversity conservation in this context is nuanced. On one hand, many NTFP species listed (Table 3) are keystone resources in the forest ecosystem. For example, the Mahua tree is a keystone of dry deciduous forests: its flowers are a crucial food for many animals and its fruit and seed feed wildlife [135][136]. By valuing mahua, communities have a reason to protect those trees, which in turn benefits the ecosystem (pollinators, soil enhancement from leaf litter, etc.) [135][137]. Similarly, the Palas tree not only has cultural importance but is the primary host for lac insects; conserving Palas has biodiversity benefits and carbon sequestration, etc. [51][52]. We see evidence that when given a stake (like lac cultivation), villagers indeed tend those trees carefully. This corroborates the idea that sustainable NTFP harvesting can align with conservation – provided the harvesting is done in a way that doesn’t irreversibly damage the resource. Best practices, as cited in various guidelines, include things like not over-harvesting fruits (leave some for regeneration and wildlife), rotational harvesting areas, and value addition that uses parts without killing the plant (e.g., collecting resin or fruits instead of cutting trees) [138][139]. In our community, some of these practices are informally known (for instance, they say never to pluck all the amla from a tree; leave some so the tree “doesn’t get angry” – a traditional conservation ethic). Formalizing and reinforcing such practices through training or rules in the community could ensure NTFP use remains sustainable.

At the same time, we must note that commercialization poses risks if not managed. For example, Chironji being vulnerable is a caution – a commercial market can drive unsustainable extraction unless harvest controls are in place. If tomorrow a big pharma company created huge demand for Gudmar leaves (Gymnema) from this area, a free-for-all harvest could decimate the local populations. Thus, any intervention to increase NTFP-based income should be coupled with community-based resource management plans. This is where institutions like Joint Forest Management Committees (JFMCs) or the Gram Sabha under the Forest Rights Act can be vital. They could monitor the resource, set quotas or seasons, and ensure regeneration efforts (like planting of fruit tree species or protecting saplings). The local Forest Department could play a facilitating role here by providing seedlings of key NTFP species for enrichment planting in degraded areas, which would both restore forest cover and future NTFP yield.

4. Market and Institutional Support – bridging the gap: The barriers identified (market access, low prices, processing, etc.) are not unique – they echo findings from numerous NTFP value chain analyses in India (e.g., one study in Odisha found similar issues for sal seeds and kendu leaves). What has been lacking historically is strong institutional support at the grassroots. However, there are now initiatives aiming to change that: The Minimum Support Price (MSP) for MFP scheme introduced by the Indian government in 2013 and expanded in 2018 is a major policy step[107]. It sets floor prices for 49 forest products as of 2020 and channels procurement through state agencies (like MP Tribal Federation). In theory, this protects gatherers from distress sales and price volatility. In practice, awareness of MSP among our respondents was low; only the tendu and sometimes mahua collection was linked to any formal price mechanism. This suggests a need for better outreach so that villagers actually demand and utilize the MSP scheme. States like Chhattisgarh have had some success by actively procuring tamarind, mahua, etc., through cooperatives at MSP [93][96]. Madhya Pradesh could strengthen similar efforts via its Laghu Vanopaj (Minor Forest Produce) Federation.

Another key program is the Pradhan Mantri Van Dhan Yojana (PMVDY), which envisages setting up Van Dhan Vikas Kendras – clusters of SHGs for processing and marketing NTFPs. If one were established in our study area, it could address several barriers by providing infrastructure (drying, storage, processing equipment), training, and linkage to markets (perhaps through tribal department outlets or e-commerce of tribal products). The hesitation or slow uptake locally might be due to the nascent stage of the program or bureaucratic delays. Our results underscore community interest in such support: many respondents, when told about the idea of collectively processing and selling, were enthusiastic – “if sarkar (government) gives machines and takes our goods to sell in big cities, we will gladly do the work,” said one SHG member. This indicates that the barrier is not unwillingness but lack of initiative and trust. A policy implication is that extension agencies or NGOs need to work on trust-building and demonstrating quick wins (like the mushroom powder SHG example) to galvanize more participation.

5. Aligning Livelihood Improvement with Conservation: The broader significance of making NTFP livelihoods sustainable is that it can reduce pressures on wildlife and forests from less compatible activities. For example, if forest villagers earn well from collecting fruits and seeds, they might have less incentive to resort to illegal logging or poaching (activities sometimes driven by desperation). In our area near Kanha, human-wildlife conflict and restrictions cause resentment; giving people a legal, profitable stake in the forest (like managing mahua orchards or beekeeping for honey) can turn them into stakeholders in conservation. It’s basically operationalizing the concept of “conservation by utilization” – the idea that controlled harvesting of renewable resources can finance conservation and provide local benefits, a concept long discussed in sustainable development literature (WCED, 1987).

That said, there are trade-offs and policy must navigate them. A critical one: the forest department often fears that promoting NTFP collection could lead to over-extraction or habitat disturbance (like frequent human presence could disturb wildlife in a tiger reserve buffer). These concerns are valid, so a balance must be struck – e.g., designating certain zones for intensive NTFP management while leaving core areas undisturbed, or rotating harvest areas. Our study area being in a buffer zone means sustainable use is allowed by law, but it requires planning. Policy could encourage participatory resource monitoring – involving villagers in tracking the health of NTFP species and adjusting harvest accordingly (citizen science approach).

6. The case for value addition and entrepreneurship: One of the brighter spots is the possibility of moving up the value chain. The success of lac cultivation historically and the recent attempts at mushrooms and mango products illustrate that raw NTFPs give only a fraction of the potential value to locals [103][140]. If communities can perform first-level processing (drying, grading, pulverizing, packaging), they can command better prices and create local employment beyond just collectors (like packaging operators, etc.). For instance, if instead of selling raw mahua at ₹25, they distill it into a packaged beverage or bake it into a cookie, the value multiplies (some entrepreneurial tribals in a different part of MP have started selling mahua cookies under a brand, showing innovation). The challenge is that entrepreneurship skills and capital are limited in such villages. This is where collaborations can help: either cooperatives or public-private partnerships where a company could source from a village enterprise at fairtrade prices. The Hindustan Times report on “heritage mahua liquor” initiative indicates that the government attempted something like this – supporting SHGs to produce bottled mahua liquor as a premium product [141][142]. It ran into marketing issues and demand shortfall, but it’s a pilot to learn from. Perhaps marketing should highlight the cultural story to urban consumers (e.g., telling the tale of Baiga brew to create niche demand) – a space where NGOs and social enterprises can be creative.

7. Income vs. conservation – an equilibrium to find: There is evidence from our study that some NTFPs (like tendu leaves) are being managed in a fairly sustainable way under the state system, but they yield low income; others (like chironji) yield higher income per unit but might be causing resource strain. The goal should be to enhance incomes from those resources which can sustain higher harvest levels (e.g., truly abundant ones like invasive weeds – though none were focus here, a tangent: some communities make baskets from lantana invasive or briquettes from weeds – converting a problem to income). For our context, promoting those NTFPs which are farmable or enrichable might be key – e.g., encouraging villagers to plant more Phyllanthus emblica (amla) on community lands or their own lands can both increase supply and take pressure off wild trees. Agroforestry of NTFP species is a promising avenue: if Baiga farmers plant say 20 mahua or amla trees on their farm boundaries, in a few years they have a sustainable source without needing to forage far, and it adds tree cover. This aligns with India’s Green India Mission which supports tree-based livelihoods [143].

8. Policy Implications Summarized: Our case study leads to several policy recommendations, which we will enumerate in the next section. In essence, it calls for an integrated approach: secure the resource (through community forestry and sustainable harvest plans), build the capacity of people (through knowledge revival and new skills for processing), link them to markets (through MSP, cooperatives, or private channels), and ensure that the benefits flow equitably to the primary collectors. When these elements come together, NTFPs can truly be drivers of both improved livelihoods and incentives for conservation, turning what is currently a vicious cycle of poverty and resource decline into a virtuous cycle of empowerment and stewardship.

Policy Implications

Drawing on the study findings, we outline key policy and programmatic interventions that could enhance the role of NTFPs as sustainable livelihood drivers while safeguarding the forest ecosystem. These recommendations are relevant not only to the Balaghat/Baherakhar context but broadly to similar forest-dependent communities:

1. Strengthen Community-Based NTFP Management: Empower the local Gram Sabha or community forest committees to manage NTFP resources. Under India’s Forest Rights Act (2006), communities can claim rights to forest produce and manage them sustainably. Implementing this by training committees in making simple management plans (e.g., mapping where mahua trees are, deciding rotational harvest or protection of regenerating saplings) will give villagers a sense of ownership. For instance, the community could decide that each household is assigned certain mahua trees to care for and harvest, preventing the tragedy of commons. The Forest Department can shift to a facilitator role – providing toolkits for sustainable harvest (like climbers, nets for fruit collection to avoid cutting branches, etc.) and monitoring assistance rather than a policing role. Where needed, scientific inputs from researchers (e.g., on how much to harvest without harming regeneration) should be integrated into community practices [139][144].

2. Revitalize Traditional Knowledge and Integrate it with Modern Science: Launch programs to document and disseminate indigenous knowledge of NTFPs, especially medicinal and nutritional knowledge. This can include creating community knowledge registers in local language, supporting inter-generational learning (perhaps through school projects that have students interview elders about NTFPs), and recognizing knowledge holders (like honoring the village healer to raise their profile). Additionally, value validation – scientific studies on the nutritional content of local wild foods or medicinal efficacy of herbs – can legitimize traditional claims and even create new markets (e.g., if a local berry is found extremely high in antioxidants, it could be branded as a superfood). Combining traditional wisdom with modern packaging (such as herbal teas or nutraceuticals) can open niche markets that command premium prices, with a share going back to communities.

3. Improve Market Access and Price Realization: This has several facets. Expand MSP for MFP procurement – ensure that announced MSPs (like those in Table 4) are actually operational on ground in each village cluster. This might involve increasing the number of procurement centers, simplifying procedures, and timely payments. The tribal development department could set up seasonal collection camps in villages during harvest time so people can directly sell at fixed rates. Promote Cooperative Marketing: Encourage and assist villagers to form cooperatives or producer companies specifically for NTFPs. These entities can aggregate produce, maintain quality, and directly negotiate with buyers or even export. Government and NGOs should provide legal and financial help to set these up. For example, a “Baiga Forest Produce Cooperative” could brand products like “Baiga honey” or “Baiga herbs” which tells a story and appeals to ethical consumers. Leverage E-commerce and Urban Markets: In the digital age, even small tribal enterprises can access larger markets through platforms like Tribes India (a government-run retail chain for tribal products) or online marketplaces. Policies can provide them training on e-commerce and possibly subsidize the initial marketing costs. A success story from Northeast India is how wild tea and herbal products by tribal groups reached global customers online; a similar model can be tried here.

4. Build Local Value Addition Centers (Van Dhan Kendras): Operationalize the Van Dhan Vikas Kendra scheme in this cluster. Concretely, that means establishing a facility with drying yards, storage godowns, oil expellers (for seeds like mahua, neem), grinding machines (for powders), packaging unit, etc., managed by a cluster of SHGs. The capital expenditure could come from central schemes (PMVDY grants) and state tribal department, while technical training can be given by experts from institutes like Indian Institute of Forest Management or agriculture universities. These centers can focus on a few high-potential products: e.g., Mahua – making value-added products like mahua jam, mahua health tonic (there have been experiments blending mahua with other ingredients to make a non-alcoholic health drink); Amla – producing amla candy, pickles, or juice which have good market; Tamarind – processing into concentrate or deseeded cakes for culinary use; Herbal teas from forest leaves (like mixing gudmar, tulsi, etc.). Each of these can significantly increase incomes. Such processing also reduces physical volume, making transport easier from remote areas. Governments should also ensure these centers have access to working capital so they can buy raw NTFPs from members at fair prices and hold stock to sell when prices are better.

5. Provide Training and Extension Services: Many tribal collectors have spent generations in forests but lack exposure to market demands (like grading or hygiene standards). Regular workshops should be held on sustainable harvesting techniques (to improve yields without harm) and post-harvest handling (proper drying, sorting, not mixing varieties, etc.). For example, training on improved honey collection methods (using protective gear and smokers that do not char the honey) can both increase quantity and quality of honey, and make it organic-certified. Training women in packaging and simple quality testing (like moisture content for dried products) will empower them to ensure their products meet market standards, hence commanding better prices [145][146]. Additionally, entrepreneurship development workshops can inspire some community members (especially youth) to take initiatives – e.g., a young Gond might start a small business of crafting and selling leaf plates or pottery with NTFP additives, etc. Government could tie up with organizations like TRIFED or NABARD to run such capacity-building programs in the area.

6. Enhance Financial Support and Insurance: One reason people shy away from full-time NTFP business is risk – if the crop fails or prices crash, they have no safety net. To mitigate this, policies could introduce NTFP collectors’ insurance or risk funds. For instance, if a mahua flowering is destroyed by untimely rain, an insurance scheme could compensate collectors similarly to how crop insurance works for farmers. Also, facilitating micro-credit to SHGs or cooperatives to invest in processing or to hold stock when prices are low would help them avoid distress sales. Government-backed low-interest loans or grants under programs like Start-Up India could be earmarked for tribal entrepreneurs focusing on forest products.

7. Conflict Resolution and Resource Rights: Since these villages are near a Protected Area, ensure that the buffer zone regulations allow sustainable NTFP use (as per WLPA, buffer areas can have regulated resource use). Clear communication from forest authorities about what is allowed (perhaps a list of NTFPs that can be collected, and quantities) will prevent harassment. Simultaneously, involve the community in patrolling and protecting the forest against outsiders or illegal timber felling – basically integrate them into conservation efforts with incentives. If the park authorities employ locals in activities like fire prevention, invasive species removal, etc., it provides additional livelihood and aligns their interest with conservation. One policy idea is to share a portion of tourism revenue or conservation grants with communities that are actively conserving NTFP resources (akin to benefit-sharing models in some African community conservancies). Knowing that conservation yields direct monetary reward can change attitudes from viewing wildlife protection as a hurdle to seeing it as a partnership.

8. Monitor and Research: Implement a system to monitor NTFP populations and harvest levels. This could be done by local youth trained as para-ecologists, in collaboration with researchers. Over time, data on how much is being extracted vs. how the resource base is faring will inform adjustments needed. For example, if a certain medicinal herb shows decline, they might impose a temporary harvest moratorium or cultivate it in home gardens. Policymakers should also invest in NTFPs. For example, cultivation trials for chironji or medicinal plants like Chlorophytum (Safed musli) have been done elsewhere – promoting such cultivation on degraded lands or farm boundaries can reduce wild pressure and increase supply sustainably.

9. Holistic Rural Development: Finally, it’s worth noting that NTFP development should be part of a broader rural development plan. Parallel investments in improving agriculture (e.g., introducing drought-resistant crops or minor irrigation so that people aren’t as wholly dependent on forests for survival) and in education/health create an enabling environment where people can engage in NTFP enterprises by choice and not desperation. For the Baiga and Gond, who often face marginalization, affirmative actions like market reservations (government could mandate procurement of some herbal products from tribal groups for public distribution) or adding NTFP-based nutrition in government nutrition programs (like Anganwadi centers could use local forest foods in the meals, providing market and nutrition) could be game-changers.

In conclusion, the policy direction should be to recognize forest dwellers as stakeholders and experts in their ecosystem, not as encroachers or mere laborers. By investing in their capacity and giving them rights and responsibility, we harness their traditional wisdom for modern sustainability goals. The findings from Baherakhar show the latent potential – with supportive policies, what is now a subsistence activity could become a sustainable enterprise that keeps both community and forest healthy.

Conclusion

This study has examined the twin themes of sustainable livelihoods and biodiversity conservation through the lens of non-timber forest products in a tribal community context. Focusing on the Gond and Baiga communities of central India, our research highlights a situation that is at once challenging and hopeful. On the one hand, these indigenous communities continue to face economic marginalization, with NTFPs currently providing only modest supplements to their livelihoods. Traditional knowledge that once ensured sustainable use of a rich array of forest products is fading under the pressures of modernization, reduced forest access, and changing aspirations. The people have, in many ways, become less connected to the forest for daily living than they were a generation ago – a trend that, if unaddressed, could bode ill both for their cultural-ecological heritage and for the forests that thrive under human stewardship.

On the other hand, the study reveals significant untapped potential: the forests around Baherakhar still harbor diverse and valuable NTFPs, and the community – especially its women and youth – are keen to improve their economic lot if given the opportunity and support. We see that with the right interventions, NTFPs can become a conduit for positive change. For the community, developing NTFP-based enterprises (like processing mahua, tamarind, herbs, or honey) could mean new jobs, higher incomes, improved nutrition, and empowerment – essentially leveraging their natural heritage for development in a sustainable manner. For the forest, a scenario where local people derive substantial benefits from non-destructive use creates a powerful incentive for conservation: forests will be seen not just as restricted spaces for wildlife, but as a source of prosperity that merits protection. In policy terms, this aligns with India’s vision of inclusive conservation – securing livelihoods while protecting ecosystems – as reflected in programs from the national Green India Mission to state-level joint forest management and tribal welfare schemes [143][34].

The key message from our case study is one of integration. Integrating traditional knowledge with scientific approaches can yield sustainable harvesting practices; integrating community efforts with institutional support can overcome market hurdles; integrating livelihood objectives with conservation planning can ensure that each reinforces the other. For instance, when a Baiga woman is able to earn dignified income by making herbal products from the forest, she becomes an ambassador for conservation – her success depends on a healthy forest, and she will champion its cause. Conversely, a forest that is simply locked away from local use may conserve biodiversity in the short term, but in the long run it risks losing its stewards and may fall prey to neglect or illicit exploitation.

It is often said that forests are not just flora and fauna – they are also about people. Our study underscores that in the context of central India’s tribal heartland. The livelihoods of the Gond and Baiga are inextricably tied to the rhythms of their forest landscape. Even as they adapt to modernity, these communities carry forward a legacy of living with the land. By empowering them to use that legacy in new ways – through entrepreneurship, cooperatives, and participatory conservation – we address multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at once: eradicating poverty (SDG1) and hunger (SDG2), promoting good health (SDG3) through traditional nutrition and medicine, achieving gender equality (SDG5, since women are often primary NTFP collectors and would benefit from these initiatives), reducing inequalities (SDG10) by giving marginalized tribes a viable economic pathway, fostering responsible consumption and production (SDG12 via sustainable harvesting), taking climate action (SDG13 as forests are carbon sinks), and conserving life on land (SDG15) [7][10].

In conclusion, the case of NTFPs in Baherakhar offers a microcosm of a broader paradigm: finding solutions that are ecologically sound, economically feasible, and culturally respectful. It demonstrates that non-timber forest products – often overlooked in mainstream development dialogues – can indeed act as drivers of sustainable livelihoods and allies of conservation, provided the right supportive environment. The road ahead should build on the insights from this study and similar ones: engage communities as equal partners, invest in local capacities, create enabling market and policy conditions, and continuously strive for the balance between use and care. If this can be achieved, the forests of Central India will not only remain biodiverse havens for tigers and trees but also flourish as the backbone of human well-being and cultural vibrancy for the Gond, Baiga, and many others who call these forests home.