Millets Pathway to Sustainable Development and Entrepreneurship: A case study from Baherakhar Tribal Village of Balaghat District, Madhya Pradesh, India

26.11.2025

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

Integrated Development Organisation

OTHER CONTRIBUTING ORGANIZATIONS

Indian Institute of Forest Management

DATE OF SUBMISSION

08/2025

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

India

KEYWORDS

Millets, Tribe, Traditional Knowledge, Baiga, Livelihood

AUTHORS

Ajoy K Bhattacharya, Chairperson, IDO and IFS (Retd)

Anjali, MBA, Sustainability Management, IIFM

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

1. Background

The study was conducted in Baherakhar village of Balaghat, M.P. Balaghat is densely covered by forests, approximately 4775.54 sq. km and the tribal population is around 17,146, which is spread among 190 villages [Chakma T et al.,2014]. It is endowed with natural resources like teak, sal and tendu trees. These villages are remotely located and quite isolated from urban cities. The major population in tribal villages is of Baiga tribe. Due to poor literacy rates and poor levels of awareness, the Baigas are unable to find stable employment and are exploited as labourers, which fetches them meagre income. This is also because of their low negotiation capacity as they are perceived as ignorant and poor. Because of low employment, almost all villagers were caught in the trap of debt. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that the households were buying and consuming food of the required quality or quantity. Poverty restricts the number and the quality of their meals as well as cooking methods [French SA et al.,2019]. The decision to buy food items in poor households is dictated more by affordability than by nutritional value. The absence of a stable source of income leaves them in abject poverty, to the extent that they could barely afford two square meals, let alone complete nutrition. There is a big question mark on food security among all households as they live hand–to–mouth. If they cannot find any job or there is a sudden expenditure due to some medical condition, it poses a challenge to their food security.

In the study area, there were 10–20 homes per village on average. There were approximately 2–3 tolas (a group of about four to six homes is called ‘tolas’) in each village. A few tolas had a mixed population of different tribes. Baherakhar village, nestled in Balaghat District, has a long-standing history of agricultural practices deeply rooted in millet cultivation. Millets, such as Kodo, and Kutki, have thrived in this region for generations, providing sustenance, income, and cultural significance to the community. These small-seeded grains are known for their resilience, adaptability to diverse climatic conditions, and nutritional value. However, the traditional cultivation and consumption of millets in Baherakhar village have experienced a gradual decline in recent decades. This decline reflects broader trends observed in various regions, where traditional crops are being replaced by cash crops or high-yielding varieties of other grains. Several factors have contributed to this decline, encompassing socio-economic, environmental, and cultural aspects. Socio-economic changes have influenced farming practices and land-use patterns in Baherakhar village. Farmers, motivated by market forces and the pursuit of higher profits, have gradually shifted their focus from millet cultivation to cash crops or commercial grains that offer better financial returns. This transition has resulted in a reduced area of land dedicated to millet cultivation and a decline in overall production.

Millets are the powerhouse of nutrition like protein, essential amino acids, vitamins, and minerals. They are a group of highly nutritious and adaptable grains, to improve lives, promote environmentally friendly practices by emitting less greenhouse gases, improve soil health, and support crop rotation. Historically, millets have played a crucial role in global food security due to their hardiness and nutritional value. Despite their potential to support sustainable agriculture and livelihoods, there’s a lack of research on effective ways to preserve and manage millet. Millets offer a significant solution to environmental challenges. These ancient grains are not only packed with nutrients but also require fewer resources to grow. Shifting to millet-based agriculture can lower production costs, conserve water resources, protect soil health, and make our farming systems more resilient to climate change.

Additionally, The UN declaring 2023 as the International Year of Millets brought much-needed global attention to these grains. This initiative aimed to educate people worldwide about the nutritional benefits of millets and their potential contribution to sustainable development as millets are climate-resilient crops. India’s G20 Presidency sets an inspiring and optimistic pathway for all nations to attain agricultural efficiency and food security through millets. G20 India’s actions put a spotlight on millets, potentially leading to increased research and development in millet cultivation and processing, support for millet farmers and businesses, greater consumer awareness, and incorporation of millets into diets.

2. Research objectives

- To analyze the historical significance of millets in the area and understand their role in the local economy and dietary patterns.

- To assess the current scenario of millet cultivation in Baherakhar village, including the area of land dedicated to millet cultivation and crop yields.

- To identify and examine the reasons for the decline in millet production and usage, taking into account socio-economic, environmental, and cultural factors.

- To explore the market dynamics, consumer preferences, and demand for millets in the study area.

3. Methodology

A purposive sampling technique was used to select a representative sample of farmers from Baherakhar village. A total of 35 villagers have been selected as respondents for this case study. For collecting the data Structured surveys, interviews, and FGDs were conducted among farmers in the village. It precisely means that a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative and quantitative methods was used to collect data from the field. In-depth interviews with key stakeholders, including farmers, local authorities, agricultural experts, and market vendors gave deeper insight into the gravity of the existing situation. Quantitative data from surveys is analysed using descriptive statistics such as mean, median, SD, etc.

4. Result and Analysis

4.1 Profile of village:

All respondents in Baherakhar village had kutcha houses made of mud, and straw, and the roofs were made up of twigs, bamboo or baked clay, tarpaulin, or plastic sheets. There was one Anganwadi in each of the study villages, and one primary school in the study village. The respondents were enquired if they had the basic documents like a ration card (used for buying grains, and pulses from the PDS system at subsidized price) or, an Aadhaar card (which can be used as proof of identity throughout India). Under the Direct Benefit Transfer Scheme, the government transfers the benefit money directly to the bank account of the beneficiary. Still, if the beneficiary does not have any identity proof for opening a bank account, it becomes difficult for them to get any benefit from the government or work in employment generation programs like MGNREGA. Many of them did not have any such documents. This deprives them form availing benefits like subsidized ration from the PDS and employment under MGNREGA, which has consequences on their economic situation and hence food security.

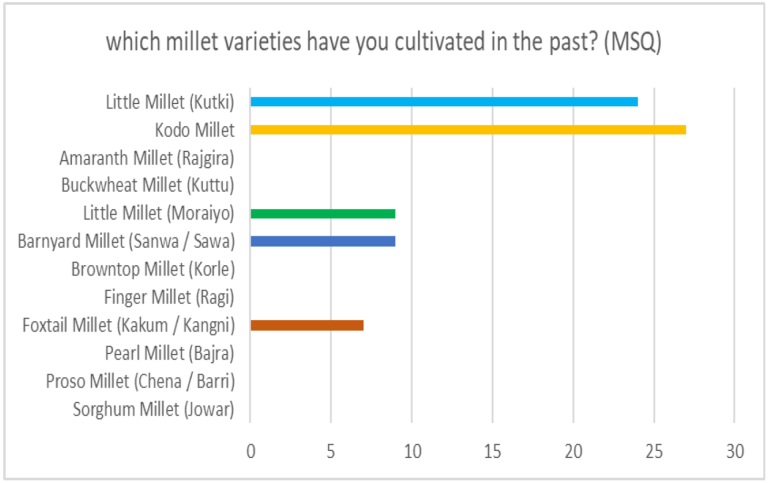

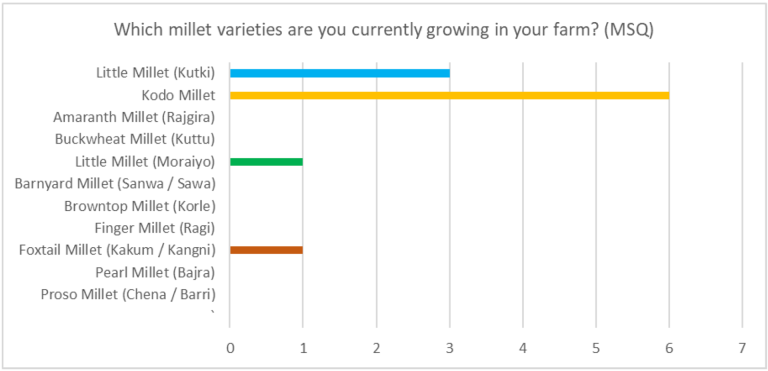

Based on the survey and Focus Group Discussion (FGD) with 35 households, it was found that currently, four different types of millets are being cultivated in Baherakhar village: Kodo, kutki, morayio, and kangni. However, there is no sawa being grown at the moment. A decline in the number of households involved in Kodo and kutki cultivation compared to the past was evident from the data.

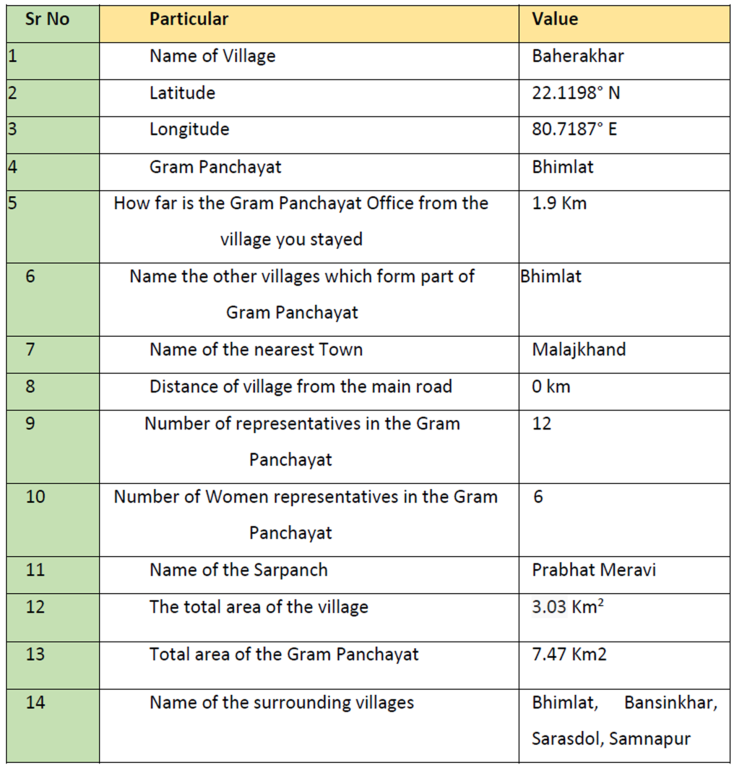

Table 1: Village Profile

Figure 2 provides a detailed location map of the village, showcasing its precise geographical position and surroundings. This map offers a detailed visual representation of the village’s placement within its broader context, highlighting nearby landmarks, geographical features, and neighbouring areas. It serves as a valuable tool for understanding and navigating the village’s specific location and its relationship with the surrounding regions.

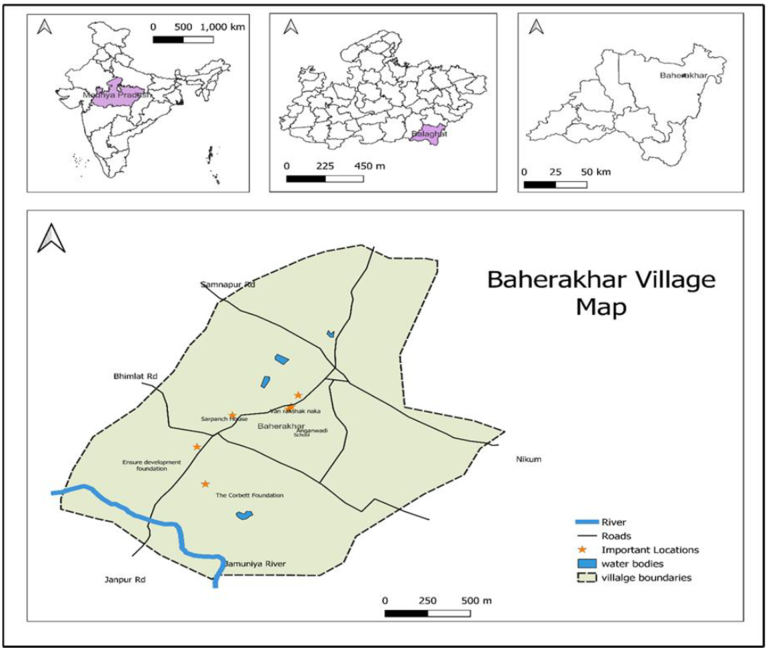

The contour map of Baherakhar village (Figure 3) displays a range of elevation levels, with the highest point marked at 554 meters above sea level and the lowest point marked at 486 meters above sea level. The contour lines on the map connect points of equal elevation, providing a clear visual representation of the terrain’s undulating nature. The highest point at 554 meters offers stunning panoramic views of the surrounding landscape, while the lowest point at 486 meters encompasses water bodies, contributing to the village’s diverse topography.

4.2 To analyse the historical significance of millets in the area and understand their role in the local economy and dietary patterns.

4.2.1 Historical role of millets: Local Economy & Dietary Patterns

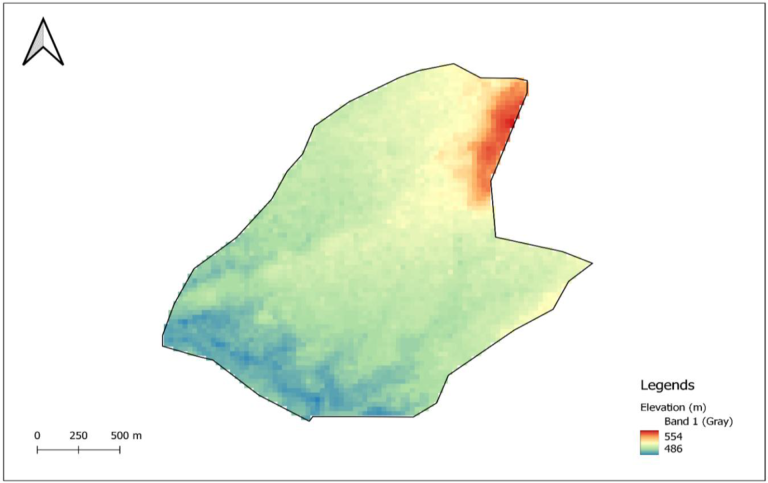

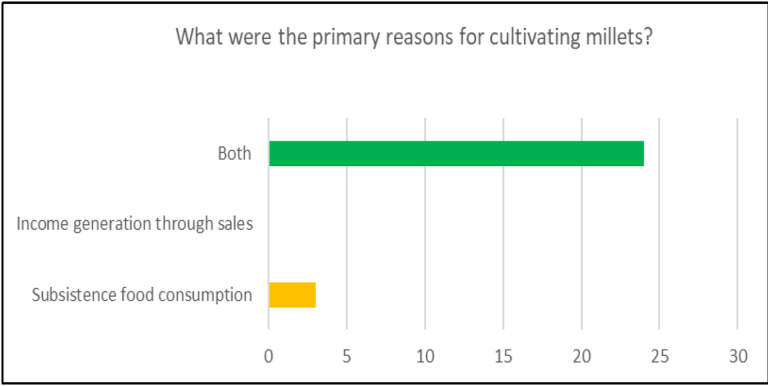

In the past Baherakhar village, millets had a crucial impact on both the local economy and people’s eating habits. Out of the 35 households surveyed, 3 households grew millets mainly for their own food consumption, while 24 households grew millets for both making money and feeding their families. This shows that millets played a significant role in the village’s economy and were also an important part of people’s diets.

During the FGD with villagers, we asked about the importance of millets in their lives. Their responses highlighted the historical significance of millet as a vital part of their daily diet. Many villagers fondly recalled cooking “Bhaat” (Kodo Rice) from kodo millet, a cherished staple food that provided nourishment for their families. They also mentioned using millets to prepare dishes like “khir” and “daliya,” showcasing the versatility of these grains in their culinary traditions.

The villagers had a strong emotional connection and fondness for millet because they recognized it as a fantastic source of nutrition. Millets are known to be very nutritious as they contain lots of fiber, vitamins, and minerals, which are essential for a healthy diet. They are said to have various health benefits, such as helping with asthma, migraines, blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes.

The graph illustrates the cultivation of five different types of millets in a village. Among the households surveyed, the highest number of households, 27 in total, were engaged in cultivating Kodo millet. Additionally, 24 households were involved in producing and selling Kutki millet, while the remaining millets like Moraiyo, Sawa, and Kangni were primarily cultivated for self-consumption purposes.

4.3 To assess the current scenario of millet cultivation in Baherakhar village, including the area of land dedicated to millet cultivation and crop yields

4.3.1 Current agricultural scenario on millet cultivation in area and crop yields

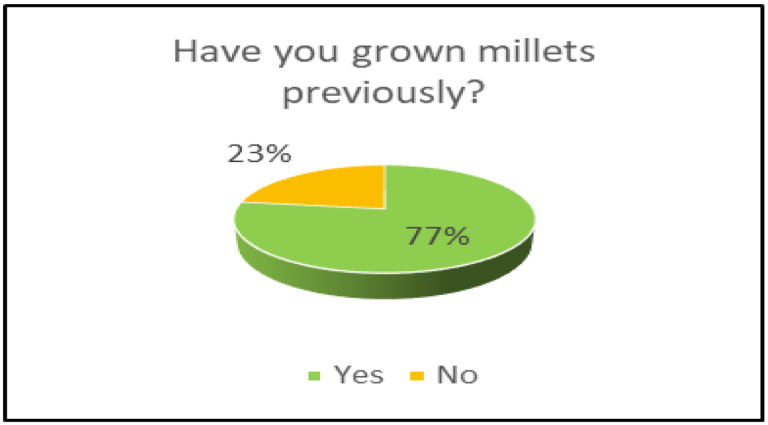

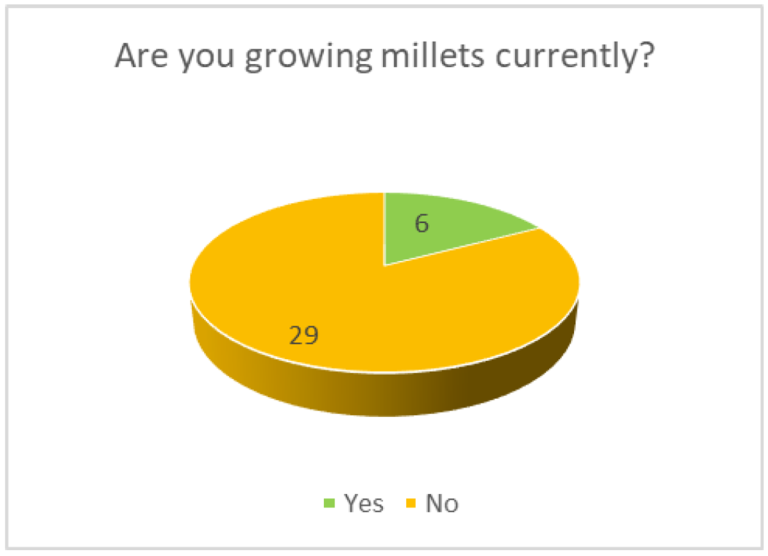

The data on millet cultivation in Baherakhar village reveals a worrying decline. Out of the 35 surveyed households, only 6 (approximately 17.14 %) are currently growing millets, while the majority of 29 households have stopped. This significant drop of about 77.78% from the past indicates a shift away from this traditional agricultural practice.

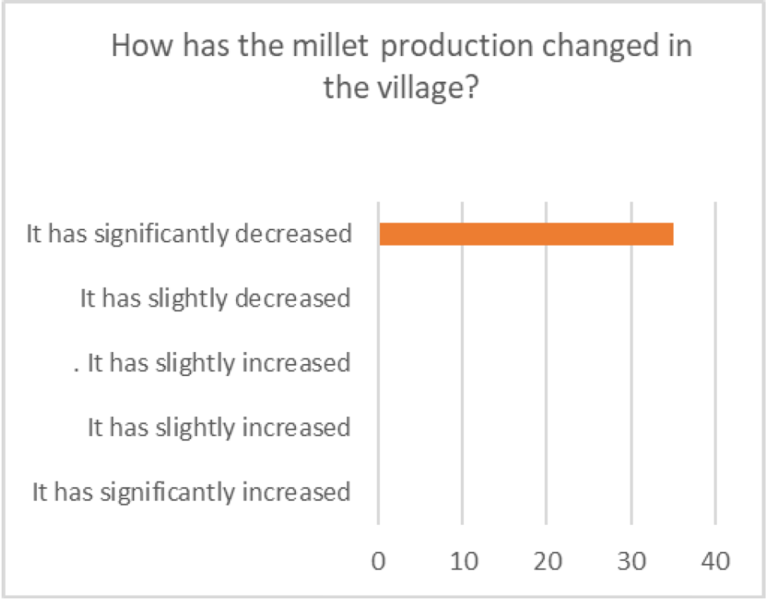

The millet production in Baherakhar village has experienced a significant decrease in the past few years. All 35 respondents reported that millet production has “significantly decreased.” This data suggests a concerning trend of declining millet cultivation and production in the village.

Figure 7: Farmers involved currently in millet cultivation

4.3.2 Type of millets currently growing in the village

Based on the survey and Focus Group Discussion (FGD) with 35 households, it was found that currently, four different types of millets are being cultivated in Baherakhar village: Kodo, kutki, morayio, and kangni. However, there is no sawa being grown at the moment. The graph also indicates a decline in the number of households involved in Kodo and kutki cultivation compared to the past.

4.3.3. Kodo millet: India is known as the place where Kodo millet originated, and it is believed that Kodo millet (Paspalum scrobiculatum) was domesticated around 3000 years ago (Arendt and Dal, 2011).m Kodo millet and kutki millet (also known as little millet, Panicum sumatrense) holds significant importance in the traditional rainfed farming systems of Gond farmers in eastern Madhya Pradesh, India (Meldrum G. et al., 2020). The best regions for growing Kodo millet are in tropical and subtropical areas (Saxena et al., 2018). This type of millet is an annual grass that typically grows to a height of about 60-90 cm. Kodo millet flowers are small and inconspicuous by nature and self-pollinated; therefore, they remain unopened. Seeds are sown from June to July (V. A. Tonapi et al., 2015). The grains of Kodo millet come in various colors, ranging from light red to dark grey, and are protected by a tough husk that can be challenging to remove.

4.3.4 Kutki Millet: Little millets known as saamai or kutki are short-duration millets and withstand both drought and waterlogging. There are three types of kutki generally cultivate in this village i.e. Bhadeli kutki, Badi kutki and Sitai kutki. Little millet is also a yearly crop having 30–90-cm hollow jointed stem with slender and robust base, leaves are linear and can be 15–50 cm in length to 12–25 cm in breadth, while the nodes are glabrous, seeds are grown during the period from June to July or between February and March (V. A. Tonapi et al., 2015). Its grain size is approximately 2.5 ∗ 1.5 mm with 1.9 g of approximate kernel weight oval in shape, and the colour is creamy with shiny appearance (J. Taylor et al., 2017).

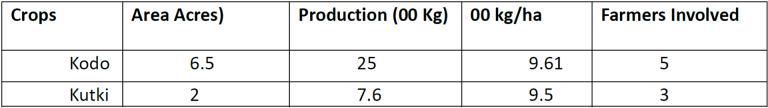

Kodo Millet is cultivated on 6.5 acres of land, yielding a production of 25,000 kg, which translates to an average yield of approximately 961 kg per hectare. This millet cultivation involves the active participation of five farmers who contribute to its growth and harvest. Similarly, Little Millet (Kutki) is grown on 2 acres of land, producing 7,600 kg, with an average yield of 950 kg per hectare. Three farmers are dedicated to cultivating Little Millet.

4.4. To identify and examine the reasons for the decline in millet production and usage, taking into account socio-economic, environmental, and cultural factors

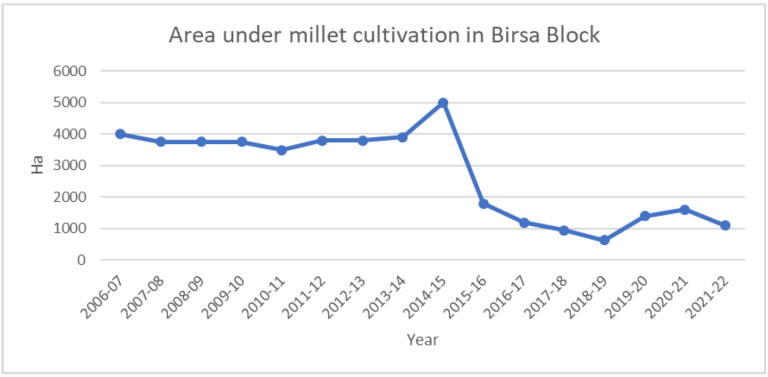

The area under millet cultivation in Birsa Bock is declined from 4000 acres in 2006-07 to 1100 acres in 2021-22. Which is also showing the decline in millet cultivation.

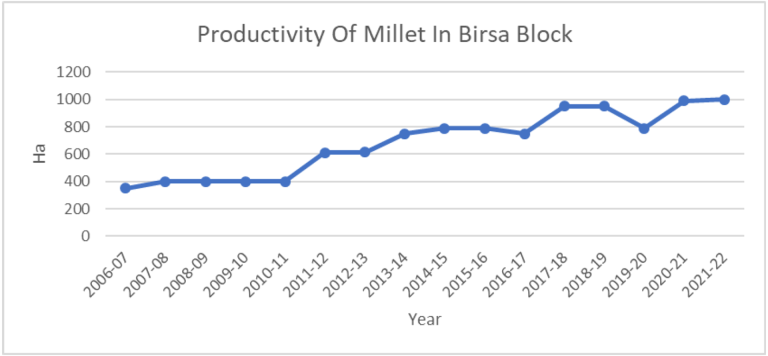

The above graph represents the productivity of millet in Birsa Block. The maximum production for Kodo is about 10 Qlt/Ha.

4.4.1 Factors Contributing to Decrease in Millet Production and Usage

The decline in millet production and usage in Baherakhar village is a significant concern that requires a thorough examination of the factors contributing to this downward trend. Millets have long been an integral part of the local agricultural practices, cultural heritage, and dietary patterns, providing essential nutrition and sustaining livelihoods for generations. However, the survey data indicates a substantial decrease in millet cultivation, with a negative impact on the community’s food security and traditional way of life. To address this issue effectively, it is crucial to identify the underlying reasons behind the decline.

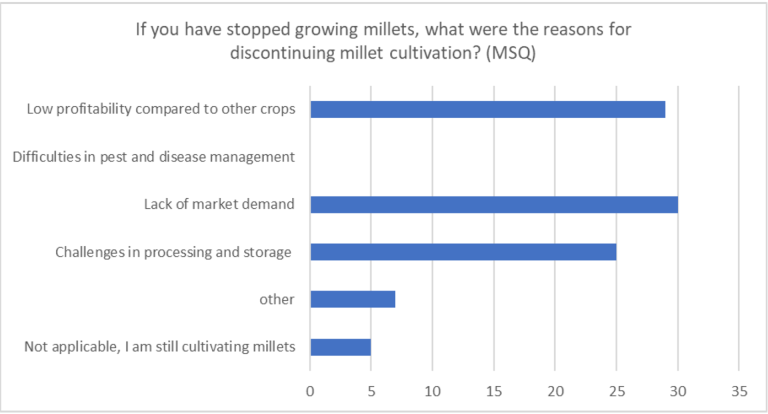

This section aims to explore and analyze the potential factors responsible for the reduction in millet production and usage. From the above graph, it appears that the majority of farmers are facing challenges and considering other options. The challenges cited by the farmers in millet cultivation include difficulties in processing and storage (25 respondents), lack of market demand (30 respondents), and low profitability compared to other crops (29 respondents). These challenges highlight the issues faced by millet farmers in the village, which might be influencing their decisions to explore other crop options.

4.4.2 Shifting Agriculture Practices

During the FGD and survey with village farmers, it was revealed that in Baherakhar village, there has been a notable transition from millet cultivation to cash crops like rice and wheat. Several factors have contributed to this shift are listed below:

4.4.2.1 Less profit

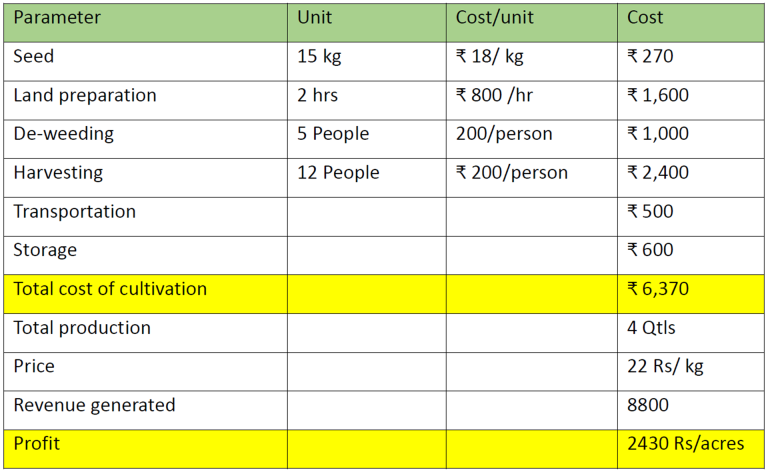

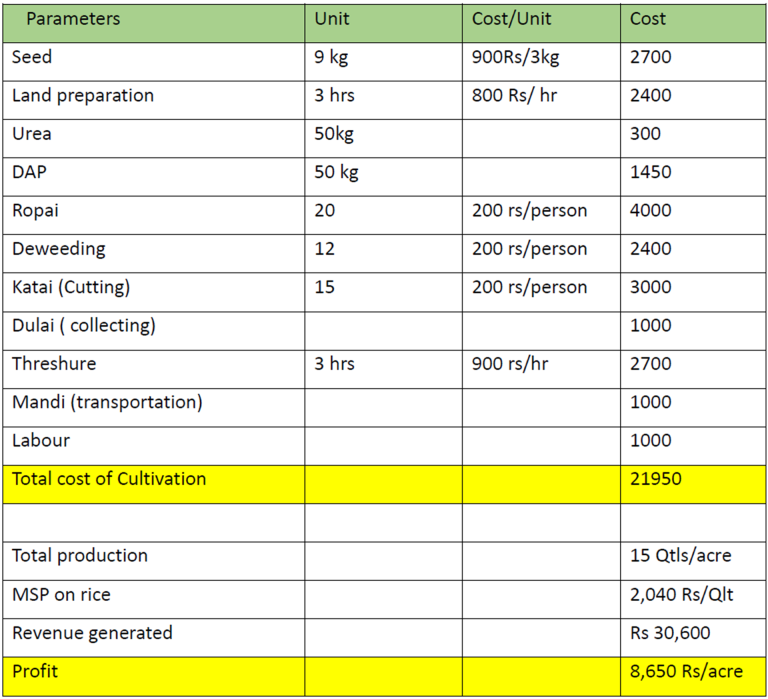

One of the primary reasons behind the shift in agriculture practices from millets to cash crops like rice and wheat is the prospect of higher profit. Farmers in Baherakhar village have recognized that cash crops offer better economic returns compared to traditional millets.

Table 3: Cost of cultivation and profit for rice.

The above calculation indicates that the profit for cultivating Kodo millet is 2,430 Rs per acre, while the profit for cultivating rice is 8,650 Rs per acre. This significant difference in profitability is one of the reasons behind the shift from millet cultivation to cash crops like rice in Baherakhar village. The higher profit potential of rice cultivation is incentivizing farmers to focus more on cash crops to improve their income and livelihood opportunities.

4.4.2.2 Consumer and Market demand

The change in consumers’ dietary choices from millets to rice and wheat has caused a corresponding shift in the market, resulting in reduced demand for millets and increased demand for rice and wheat. Consequently, farmers who used to primarily grow millets now encounter difficulties in finding a market for their millet produce. This shift in consumer preferences has a broader impact on the agricultural market, affecting the choices and challenges faced by farmers in selling their products.

4.4.2.3 Government policies

The advent of the Green Revolution brought about significant changes in agriculture, particularly in the promotion of high-yielding hybrid seeds for crops like rice and wheat. The increased productivity and higher yields offered by these hybrid varieties attracted farmers, leading to a shift away from millet cultivation. The emphasis on rice and wheat production led to a decreased focus on growing traditional millets, which were often considered less productive in comparison.

Furthermore, government initiatives like the MGNREGA played a role in encouraging farmers to convert their land from Barra land (plain field), which is characterized by poor water retention, to land suitable for paddy cultivation. This was achieved through the construction of bunds or embankments around farms, helping to retain water for longer periods and facilitating paddy cultivation. As a result, more farmers were incentivized to switch to rice cultivation due to the improved availability of water resources and the support provided by MGNREGA.

The absence of Minimum Support Price (MSP) for millets like kodo and kutki has indeed contributed to the challenges faced by millet farmers in Baherakhar village. MSP plays a crucial role in providing price assurance and ensuring a minimum income to farmers for their produce. When MSP is declared for certain crops, it gives farmers the confidence to invest in their cultivation, as they are assured of receiving a fair and remunerative price, even in times of market fluctuations.

4.4.2.4 Access to modern agricultural technologies and better infrastructure for cash crop

Access to modern agricultural technologies and improved infrastructure for cash crop cultivation is another factor influencing the shift from millets to cash crops like rice and wheat in village. The availability of advanced agricultural machinery and better farming practices has made it more convenient for farmers to cultivate cash crops efficiently and effectively.

4.4.2.5 Difficulties faced during post-harvest processing

Post-harvest processing of millets presents a significant challenge due to its labour-intensive nature. Farmers are required to manually thresh the crops, separate grains from stalks, and perform winnowing to remove chaff and debris. Moreover, de-husking and cleaning the millet grains add further to the physical demands. The absence of modern machinery compounds the issue, making this process time-consuming and physically taxing, particularly for women in rural communities who predominantly carry out these tasks. This manual labor reliance poses a significant barrier to the efficient and large-scale cultivation of millets.

4.4.2.6 Government policies and support programs related to millet cultivation

Government policies and support programs related to millet cultivation play a crucial role in promoting and revitalizing the cultivation of these traditional grains. Recognizing the importance of millets in ensuring food security, nutrition, and sustainable agriculture, both the central and state governments have initiated various schemes and measures to encourage millet farming

4.4.2.7 Madhya Pradesh Millet Mission

The Central Government’s initiatives to celebrate the International Year of Millets include offering technical and financial aid to farmers, while Madhya Pradesh’s State Millet Mission scheme provides funding, improved seeds, training, and marketing assistance to promote millet cultivation. The allocation of significant funds, 23 crores, and 25 lakhs rupees, showcases the government’s dedication to this cause. Similarly, the Agriculture Department in Birsa is promoting millet cultivation by offering subsidized kodo and kutki seeds, making it economically viable and supporting the revival of traditional crops.

4.5 Explore the market dynamics, consumer preferences, and demand for millets in the study area

4.5.1 Market:

Market linkages play a critical role in reviving millet cultivation in Baherakhar village. They involve establishing connections between millet producers (farmers) and various market actors, such as traders, retailers, processors, and consumers. The goal is to create a sustainable and an efficient market for millet-based products, ensuring fair prices for farmers’ produce and driving demand for millets in the community.

4.5.2 Sustainable Solutions for Revitalizing Millet Farming

Millet, with its high dietary nutrition and potential to enhance food security, plays a crucial role in Baherakhar village. However, the declining trend in millet cultivation is worrisome and raises concerns about its long-term sustainability. To address this challenge, we engaged in discussions with stakeholders, including farmers, local communities, agriculture experts, and NGOs. Through these collaborative efforts, we have identified and highlighted potential solutions for revitalizing millet farming.

4.5.3 Backward Linkages

a) Enhance Millet Productivity: The data obtained from the agriculture department of the Birsa block indicates a significant disparity in the productivity of Kodo-Kutki millet between Baherakhar village and the entire block. The productivity in Baherakhar village is notably lower when compared to the average productivity of the entire Birsa block.

To maximize millet productivity, improving soil health is crucial. Research data indicates that the soil in Baherakhar village lacks in Phosphorous and a few micro-nutrients. According to the villagers, this may have been depleted due to a lack of proper soil management and years of mono-cropping.

- Crop Residue Management: Leaving crop residues on the field after harvest can contribute to increasing phosphorus content over time. These residues decompose and release nutrients, including phosphorus, back into the soil.

- Organic Matter Addition: Incorporating organic matter, such as compost, green manure, or farmyard manure, into the soil can boost phosphorus content. Organic matter contains organic phosphorus compounds that break down gradually, releasing phosphorus into the soil in plant-available forms.

b) Land Utilization: The challenge of converting most fields into bunds for rice cultivation and using the remaining plain land for maize has led to the limited availability of suitable areas for millet cultivation. Encouraging farmers to grow millets alongside other crops can enhance soil health, reduce risks, and provide a diverse income stream.

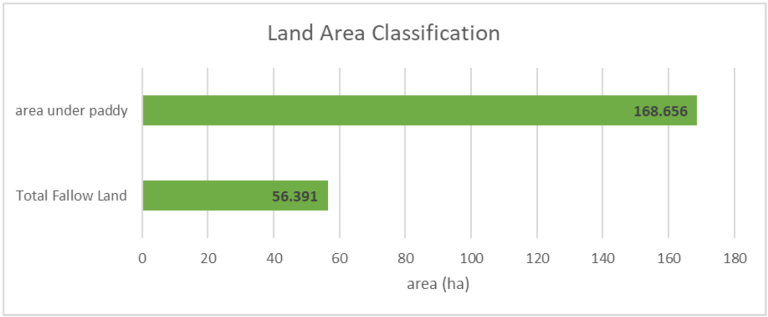

The data collected from the agriculture department of the block reveals a valuable opportunity to enhance millet cultivation in the village. The presence of significant fallow plain land indicates a potential area for expanding millet production. However, it is evident that these fallow lands are currently not being utilized effectively.

4.5.4 Price Assurance

One of the main challenges faced by millet farmers is the lack of price assurance for their produce. Unlike cash crops like rice and wheat, which have a Minimum Support Price (MSP) declared by the government, millets like kodo and kutki do not have an MSP. By creating market linkages with organizations, NGOs, or companies that are committed to promoting millet consumption, farmers can negotiate fair prices for their millet products. Paying higher prices than the prevailing market rates provides an incentive for farmers to grow millets and ensures that they receive a reasonable income for their hard work. The inclusion of jowar, bajra, and ragi in the MSP system indicates that the government recognizes the importance of supporting these millet crops and encouraging their cultivation. To promote the cultivation of a diverse range of millets and support farmers’ incomes, it would be beneficial for the government to consider extending MSP benefits to other millet crops as well. This can help in diversifying the cropping patterns, ensuring food security, and conserving traditional agricultural practices.

4.5.5 Processing and Value Addition:

By establishing strong connections between millet producers and processing units or food manufacturers. This involves transforming raw millet grains into value-added products, such as millet flour, snacks, or ready-to-eat dishes. By promoting value addition, millet products become more appealing to consumers, leading to increased demand and consumption. Encouraging farmers to collaborate with processing units will not only enhance the quality and convenience of millet products but also create a sustainable market for these nutritious grains. Due to village’s proximity to Kanha National Tiger Reserve, the region is home to several resorts. These resorts have a unique opportunity to support the local livelihood by sourcing and purchasing locally grown millet products. By incorporating these nutritious grains into their menus and creating a variety of dishes, the resorts can establish a thriving local market for millets. This not only promotes sustainable farming practices but also fosters a sense of community support and economic growth, benefiting both the farmers and the local economy. Furthermore, by showcasing millet-based dishes, the resorts can introduce their guests to the rich culinary diversity of the region, encouraging the consumption of millet and preserving its cultural significance.

4.5.6 Awareness:

Taking advantage of this year being celebrated as the International Year of Millets, awareness initiatives can be undertaken to disseminate information about the importance and advantages of millet cultivation. These campaigns may encompass diverse activities like educational workshops, seminars, social media drives, and partnerships with NGOs and agricultural entities. The collective efforts of these endeavors can play a vital role in rejuvenating millet farming, fostering improved food systems, and promoting sustainable development. In the context of millet cultivation, awareness refers to the dissemination of knowledge and comprehension regarding the nutritional value, health benefits, and adaptability of millet as a sustainable and nourishing food source. The primary aim is to target a broad spectrum of stakeholders, including consumers, farmers, and the general public, to enhance their understanding of millet’s significance.

4.5.7 Machinery

Millet processing involves partially separating and modifying the three main components of millet grain, which are the germ, starch-containing endosperm, and protective pericarp. These traditional techniques are often laborious, repetitive, and manual, predominantly carried out by women. Some of these methods have evolved to suit local tastes and fulfil specific culinary purposes. Common traditional techniques include decortication, accomplished through pounding and subsequent winnowing or sifting, as well as processes like malting, fermentation, roasting, flaking, and pounding. However, these methods are largely labour-intensive and result in products of inferior quality.

4.5.8 Government Policy Interventions

a) Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS)

Anganwadi services cater to the nutritional needs of pregnant women, lactating mothers, and young children. Introducing millet in the meals provided by Anganwadi centers can bring about notable nutritional advantages. Millets are an excellent source of essential nutrients for the growth and development of young children and nursing mothers. By incorporating nutrition programs like Take-Home Rations (THR) and hot-cooked meals, Anganwadi services can offer diverse and wholesome nutrition to their beneficiaries. This move aligns with the intention to combat malnutrition and promote early childhood development.

b) Public Distribution System (PDS)

The Public Distribution System (PDS) plays a crucial role in ensuring food security for vulnerable populations. Including millet in the PDS can have significant nutritional benefits for beneficiaries. By incorporating millet into the food basket distributed through PDS, the government can enhance the nutritional quality of the subsidized food. This move would contribute to reducing malnutrition and promoting better public health outcomes among PDS beneficiaries.

c) Mid-Day Meal (MDM) Program

The Mid-Day Meal (MDM) program aims to provide wholesome meals to school-going children, ensuring their nutritional well-being and encouraging school attendance. Integrating millets into the MDM menu can lead to numerous nutritional benefits.

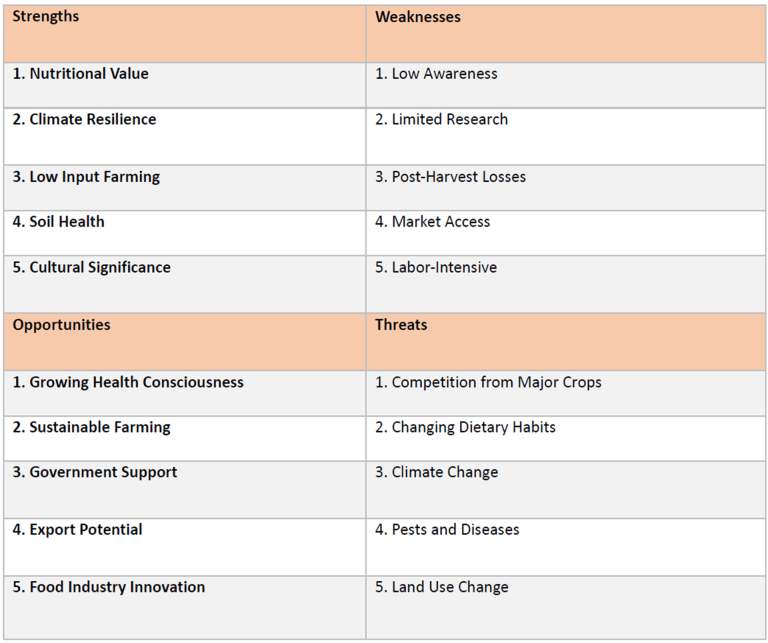

Table 1: SWOT Analysis of the proposed approaches

5. Conclusion

The case study of Baherakhar village illuminates the intricate interplay between tradition, economics, and policy in agricultural practices. Despite its longstanding tradition of millet cultivation, the village has witnessed a decline in this vital crop due to various factors, including shifts in agricultural trends, changing consumer preferences, and policy incentives favouring cash crops.

However, amidst these challenges, there lies a beacon of hope. The revitalization of millet farming presents a multifaceted opportunity for sustainable development. By fostering backward and forward linkages, encompassing soil health improvement, value addition, modern machinery adoption, and market creation, communities can breathe new life into this age-old practice. Moreover, integrating millets into government nutrition programs and public distribution systems can not only bolster food security but also preserve the cultural heritage and nutritional richness associated with these grains. Encouraging farmers to diversify their crops by reintroducing millet cultivation alongside cash crops may pave the way forward. This can be achieved through awareness campaigns highlighting the economic and nutritional benefits of millets. Lack of MSP s it has been highlighted as a major bottleneck, implementing policies that ensure Minimum Support Price (MSP) for millets will incentivize farmers to continue or resume cultivation. Additionally, providing financial assistance or subsidies for post-harvest processing equipment to mitigate challenges. Lack of awareness and capacity building has also emerged as major lacunae. Offering training programs on modern agricultural practices, including soil health management, value addition techniques, and the use of advanced machinery will empower farmers with knowledge and skills that will enhance productivity and efficiency in millet farming. Facilitating market linkages for millet producers by connecting them with potential buyers, both locally and nationally will be a key step. This all may be possible through effective community engagement. Fostering community participation and ownership in revitalizing millet farming and encouraging collective action among farmers, local authorities, and relevant stakeholders will help in to develop sustainable strategies and solutions tailored to the needs of Baherakhar village. By implementing these forward-looking initiatives, Baherakhar village can chart a path towards revitalizing millet farming, ensuring food security, preserving cultural heritage, and fostering economic prosperity for generations to come. In essence, the case of Baherakhar village underscores the importance of holistic approaches in agricultural revitalization. By marrying tradition with innovation and policy support, communities can pave the way toward a resilient, inclusive, and sustainable future, where the roots of culture and nutrition run deep.

References

- Chakma T, Meshram P, Kavishwar A, Vinay Rao P, Rakesh Babu (2014) Nutritional Status of Baiga Tribe of Baihar, District Balaghat, Madhya Pradesh. J Nutr Food Sci 4: 275.

- French SA, Tangney CC, Crane MM, Wang Y, Appelhans BM. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: the SHoPPER study. 2019;1–7

- Meldrum, G., Roy, S., Lauridsen, N.O., and King, O.E. (2020). Promoting kodo and kutki millets for improved incomes, climate resilience, and nutrition in Madhya Pradesh, India.

- Tonapi, V. A., Bhat, B. V., Kannababu, N., et al. (2015). Millet Seed Technology: Seed Production, Quality Control & Legal Compliance, Indian Institute of Millets Research, Hyderabad, India.

- Registrar General of India. (2011). Balaghat District Census Handbook 2011.

- Yadav, S., Pathak, D., & Mishra, R.P. (2018). “Socio-economic contribution of bamboo for household livelihood in Balaghat district (M.P).” International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts (IJCRT), 6(1), March 2018.

- Devi, P. B., Vijayabharathi, R., et al. (2011). Health benefits of finger millet (Eleusine coracana L.) polyphenols and dietary fiber: a review. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 51(6), 1021-1040.