Building social-ecological and climate resilience through participatory community-based forest regeneration in Krabi, Thailand

25.11.2025

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

Naturemind-ED

DATE OF SUBMISSION

07/2025

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

Thailand

KEYWORDS

Forest restoration; Biodiversity conservation; Social-Ecological Resilience; Community-based ecosystem restoration; youth impact education; nature-based solutions

AUTHORS

Pierre Echaubard, Miles Lambert-Peck, Anusit Kongoh, Wichan Anupak, Thayamon Wattanasiri, Andrea Rugo, Steven Elliot

LINK

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

Global deforestation of inland low-lying forests is accelerating. Agricultural expansion, infrastructure development, logging, and urban growth have resulted in severe biodiversity loss and disruption of climate regulation (FAO, 2020). Between 1998 and 2018, mainland Southeast Asia lost around 50% of its lowland forest cover—over 120,000 square kilometers—with only 18% of lowland areas remaining forested by 2018. Thailand now has the lowest proportion of remaining lowland forest in Southeast Asia, with only 6% of its lowland areas forested. Despite national-level bans on logging in reserved forests since 1989, market incentives for agricultural expansion continue to drive conversion. Conservation efforts have not kept pace with degradation, and remaining forest areas are highly vulnerable to further loss.

In Krabi Province, the landscape reflects this national trajectory. Extensive forest clearing took place between the 1960s and 1980s, fueled by commercial logging and migration from nearby provinces such as Nakhon Sri Thammarat, Surat Thani, and Phatthalung. Data from Thailand indicate that for every one-hectare reduction in forest cover, there is a corresponding expansion of 38.5 hectares of agricultural land or a GDP increase of USD 3.69 million—highlighting the exploitering economic forces that underpin deforestation (Tian et al., 2014; Lebel et al., 2017). As forest habitats disappeared, large mammals—including elephants, gaurs, and tigers—were locally extirpated due to hunting and shrinking habitat. Although the 1989 logging ban slowed formal extraction, conversion for plantations accelerated in response to rising global prices for rubber and palm oil. Forest protection measures, including the creation of wildlife sanctuaries and non-hunting areas, have helped preserve remaining fragments, but pressures from tourism and development continue.

The Co-ForREST program in Krabi was designed to respond to these challenges by promoting community-based restoration to recover degraded forest ecosystems, support biodiversity, and build climate resilience. The program integrates ecological restoration with local livelihoods need and transformative impact education, aiming to transform fragmented landscapes into functioning ecosystems sustained through local stewardship. Using Other Effective area-based Conservation Measures (OECM) as a framework, the project supports the conversion of plantation areas to integrated restoration and agroforestry landscapes, offering a practical and effective approach to achieving conservation goals within production landscapes.

The program supports biodiversity monitoring, seed collection, and phenology studies to inform native species selection. A nursery has been established to grow saplings, and community members receive technical training through workshops, protocols, and hands-on restoration events. Restoration sites are selected through rapid ecological assessments, and progress is monitored using clear evaluation metrics. In parallel, the program promotes environmental education by developing curricula for local schools, establishing forest learning trails, and organizing traditional knowledge walks with elders. An eco-stewardship initiative provides training for community members to lead restoration and engage in nature-based tourism, linking ecological recovery with livelihood development. The goal is to rebuild functional forest ecosystems while supporting social resilience through long-term, locally driven stewardship.

1.2. Socioeconomic, environmental characteristics of the area

1.2.1 Socio-economic characteristics

As of 2017, Krabi Province has a population of about 469,769 people. The number of households increased from 73,700 in 1998 to 113,288 in 2017. The population includes Buddhists, Thai-Chinese, Moken (sea gypsy), and Muslims. About 65 percent of people follow Buddhism, and about 34 percent follow Islam. The province has fertile land that supports rubber and palm oil cultivation. These two crops cover nearly 95 percent of all farmland. Farms include smallholdings and large plantations. Univanich Palm Oil Public Company Limited, the country’s largest palm oil producer, operates in Krabi. The company employs around 1,000 people and works with about 2,000 local growers. Krabi ranks fifth in Thailand for tourism income. Around six million people visit each year, mostly from China, Malaysia, and Scandinavian countries. Tourist numbers peak between November and April. The province has about 460 hotels, with more under development.

1.2.2. Environmental characteristics

Krabi is largely composed of karst landscapes with limestone hills and rugged terrain. The coastline, dotted with mangroves, has changed considerably over time. Erosion and sediment buildup range from -22.2 to +10.6 meters per year on sandy beaches. Changes come from wave energy, tides, and human activity. The province has a tropical monsoon climate with rainy and dry seasons. Climate change brings rising sea levels, stronger storms, and pressure on coastal habitats. The land includes some of the last lowland forests in Thailand. As of 2019, forested areas covered approximately 17.2 percent of Krabi’s total land area. Krabi is home to some of Thailand’s last remaining lowland forests, notably within protected areas such as the Khao Phra-Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary, which encompasses about 183 square kilometers. Low-lying forests are mostly tropical evergreen, with dense canopies and many plant and animal species. Forest types include primary evergreen and deciduous forest, as well as disturbed areas with bamboo and mixed deciduous trees. Lowland forests give habitat to species found only in the region, including Gurney’s pitta.

Krabi Province hosts unique limestone karst forests characterized by striking geological formations such as steep cliffs, karst towers, and intricate underground cave systems. Karst ecosystems have emerged from millions of years of limestone dissolution, forming a complex landscape distinguished by isolated habitats that drive speciation and support high levels of biodiversity and endemism. The karst forests contain specialized flora adapted to nutrient-poor and alkaline conditions, including rare orchids, cycads, pitcher plants, and diverse mosses. Fauna in these habitats is equally distinctive, ranging from cave-adapted species such as bats, swiftlets, spiders, and blind insects to primates like langurs and gibbons inhabiting the forest canopies. Krabi’s extensive caves are ecologically and archaeologically significant, harboring delicate ecosystems and historical artifacts, including prehistoric human remains and rock paintings in caves like Tham Phi Hua To.

1.3. Objective and rationale

NatureMind-ED, in collaboration with local government, community leaders, the Royal Forestry Department, the Forest Restoration Research Unit of Chiang Mai University, and international partners, has launched an integrated community-based forest restoration program around Kao Toh Luang, Chong Pli in Krabi, Thailand. The rationale behind the program lies in the urgent need to address the fragmentation and degradation of lowland forests in Krabi, where past land-use decisions prioritized agricultural expansion, tourism development, and short-term economic gain over ecological sustainability. The overarching aim of Co-ForREST is to reconnect people with forests and create opportunities for long-term stewardship grounded in local knowledge, nature-based financial models and ecosystem regeneration.

As such, the program is focused on forest restoration through biodiversity assessments, seed collection, nursery development, and technical training for local communities. Reforestation activities include restoring forest edges, monitoring outcomes, and developing site-specific protocols. Education and livelihood components center on experiential curricula in local schools, forest-based learning trails, traditional knowledge walks, and eco-steward training for community members. Core objectives with the project include building partnerships across sectors, strengthening research collaboration, and supporting policy through reports and briefings.

2. DESCRIPTION OF ACTIVITIES

In line with the conceptual framework of the Satoyama Initiative, the case study described here relies on four main operational pillars that guide our project activities.

2.1. Pillar 1: Ecosystem restoration research and implementation best-practices

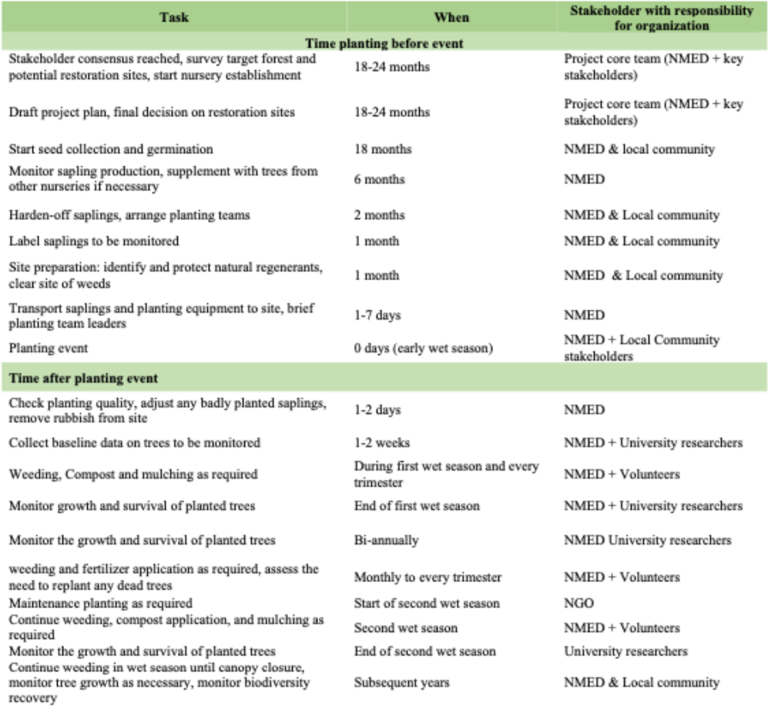

The project is grounded in scientific practice through collaboration with academic partners, including the Forest Restoration Research Unit at Chiang Mai University, to ensure methodological rigor. Restoration activities are guided by established protocols for tropical forests, with an emphasis on the Framework Species Method (FSM) and natural regeneration. The project follows a phased approach of site selection, nursery establishment, community planting, and multi-year monitoring and maintenance (Table 1).

2.1.1. Site selection

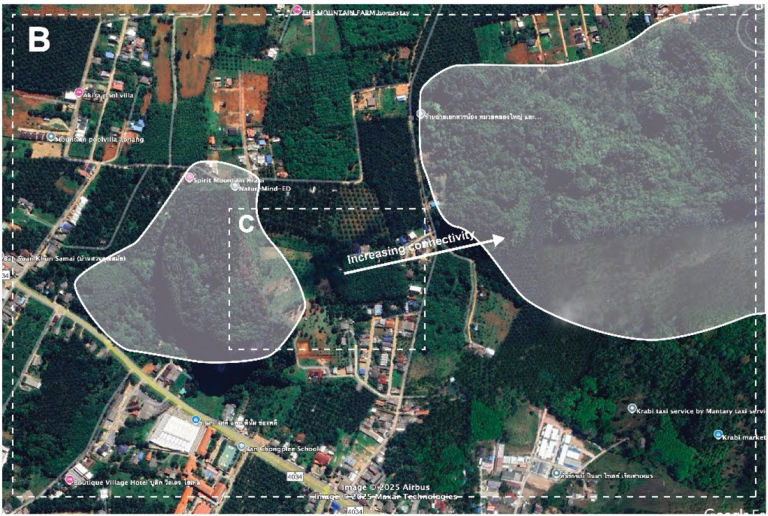

Restoration sites were identified along the edges of karst mountain formations surrounding Khao Toh Luang, with a key objective of improving ecological connectivity between two distinct karst systems (Fig. 1). Initial selection was guided by community recommendations and validated through a Rapid Site Assessment (RSA). The RSA used 5-meter diameter sampling units to count natural regenerants (tree saplings, adult trees, and coppicing stumps) and assess ground cover, which informed the number of trees required for planting.

2.1.2. Nursery establishment and material collection

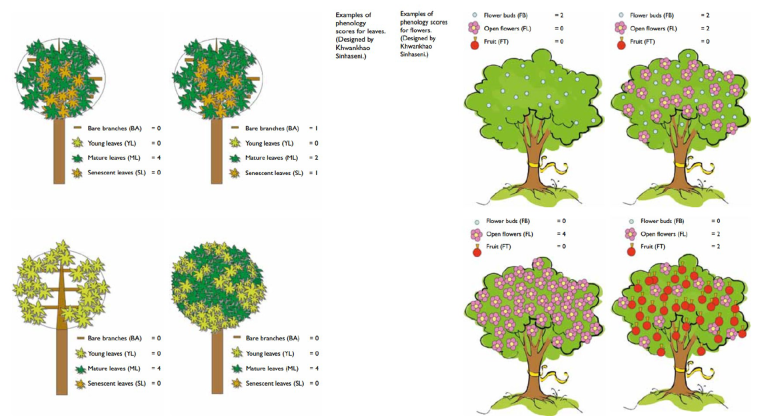

The nursery’s initial species list was based on prior research by FORRU for southern Thailand and was supplemented by surveys of local forests to identify additional framework species. We conducted monthly phenology studies (Fig. 2) on selected trees to determine the optimal time for seed collection (Newton, 1988). The nursery has developed a suite of practices including composting, specialized soil mixes, and a sapling monitoring system to ensure healthy stock for planting events

2.1.3. Tree planting, maintenance and Monitoring

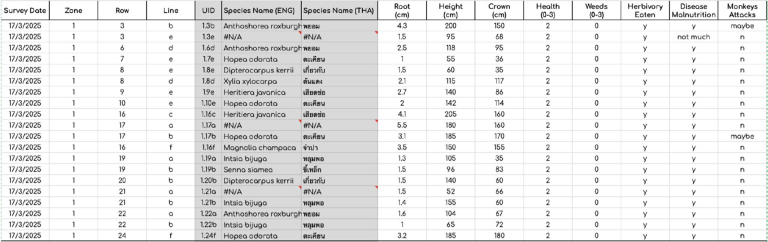

Planting events with the community were held during the rainy season to maximize seedling survival. Planted trees receive ongoing maintenance, including mulching, watering during the dry season, and protection from wildlife damage.

Tree performance is monitored twice a year by measuring survival rate, growth (height and girth), overall health, and the tree’s ability to suppress weed growth. Biodiversity recovery is tracked through baseline vegetation surveys using photo-monitoring and bird surveys using the McKinnon’s list method, as birds are the main seed-dispersers into restoration sites.

2.2. Pillar 2: Participatory community engagement methods for strategic partnership across sectors

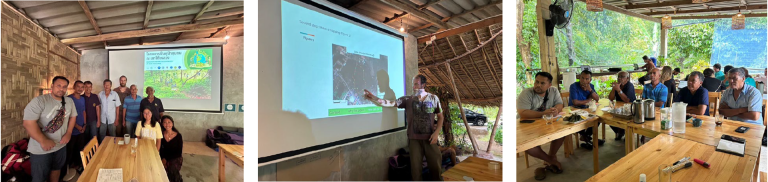

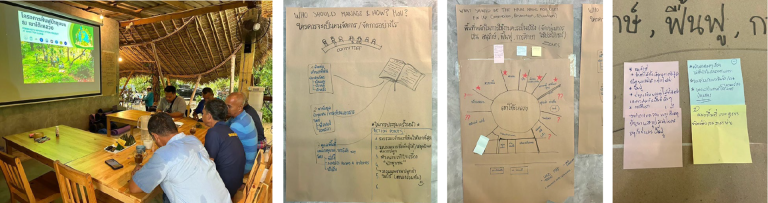

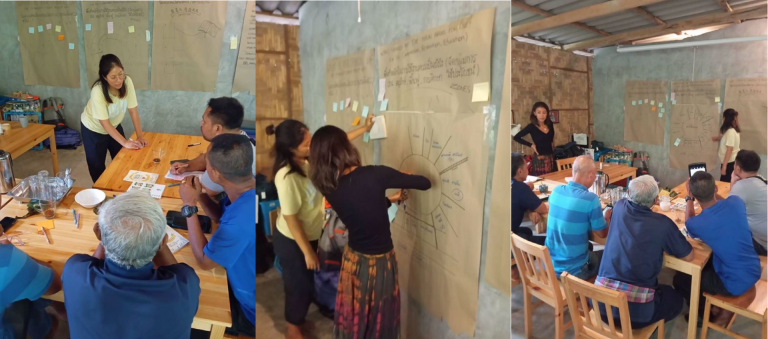

The project employs participatory community engagement methods, with a strong focus on transdisicplinarity. Participants specifically include project managers, researchers, technical advisors, landowners, local school directors, Royal Forestry Department officers, and local government representatives who serve as co-researchers and co-practitioners. Local community members and government representatives participate as co-researchers and co-practitioners, leveraging diverse knowledge systems including local wisdom, ecological expertise, and business management insights.

2.2.1. Team composition

The project’s team composition evolves iteratively through continuous snowball sampling, enhancing community acceptance and engagement.

2.2.2. Social-enterprising approach

Financial sustainability is ensured through a social-enterprise model, primarily funded by immersive educational experiences offered to international students, supplemented by sponsorships from local and international businesses.

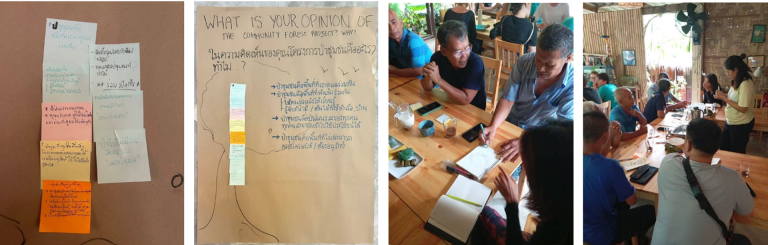

2.2.3. Community events

Community events have played a central role in both launching and sustaining the project, serving as anticipated milestones for local participants. A consistent format to each event was used as follow: 1. opening presentations in the local language to share project updates, vision and mission; 2. team-building and mindfulness games to focus attention on shared goals; 3. practical demonstrations such as seed sorting or planting techniques, hornbill nest making, etc.; 4. implementation of reforestation work; and 5. closing debriefs paired with open consultations.

2.3. Pillar 3: Youth impact experiential education activities

2.3.1. Local Curriculum development, school partnership characteristics and internships

A partnership with the local school resulted in a 16-week curriculum that promotes community development through outdoor activities like permaculture, hiking, and leadership training. The project also offers ongoing internships to local and international students to provide hands-on experience in project implementation.

2.4. Pillar 4: Research uptake and policy change

The project involves the Royal Forestry Department, the local sub-district administration, and the Krabi provincial governmentIt is also linked to the annual Krabi REWILD festival, which provides a forum for sharing expertise on regenerative development. A blueprint incorporating lessons learned has been submitted to the provincial governor to support the regional sustainability strategy.

3. RESULTS

After its inception in June 2023, Co-FOR-REST has gained strong momentum and community buy-in as well as visible forest growth.

3.1. Forest regeneration and nursery operations

The current reforestation site represents an area of 2500m2 around the Kao Toh Luang mountain, corresponding to a band of about 10m wide over 250m in length (Fig 4).

3.1.1. Rapid site assessments results

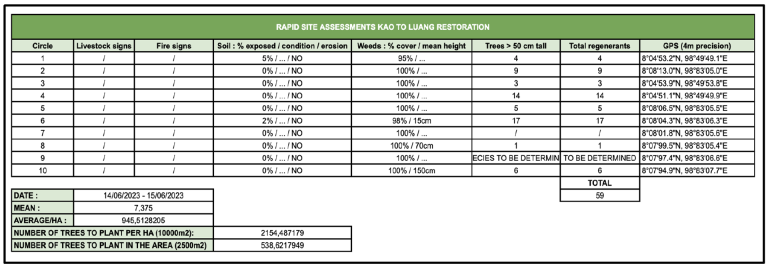

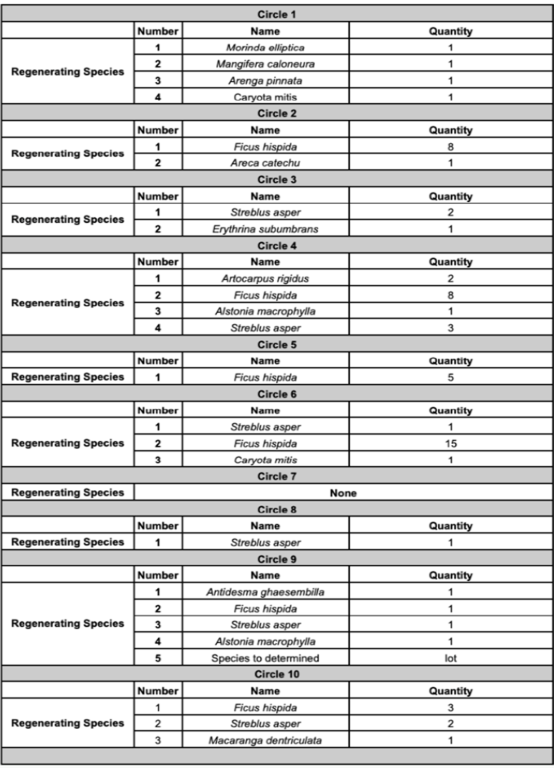

A series of 10 Rapid Site Assessments were initially performed to determine the degradation level and eventual number of trees to plant if required. We found a total of 59 regenerants (trees growing taller than 50cm) across the 10 sampling sites (Fig. 5), representing 12 species (Table 2). The estimated total number of trees to plant based on this assessment in order to match ideal regeneration density (see description in section 2.1.1.6) is 538.

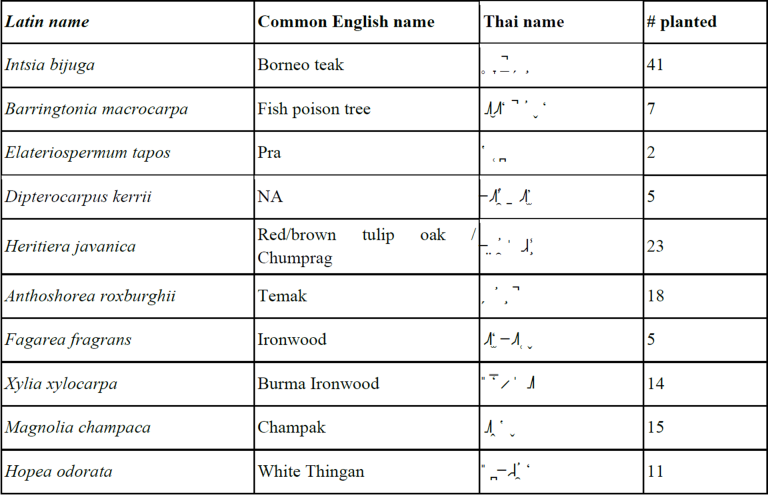

3.1.2. Framework species list consolidation and tree planted

Sapling were acquired from the Royal Forestry Department at a stage where they were ready to be planted. The first planting event was organized in October 2023. On this occasion we planted 171 trees belonging to 10 species representing 60% pioneer species and 40% climax species (Table 3).

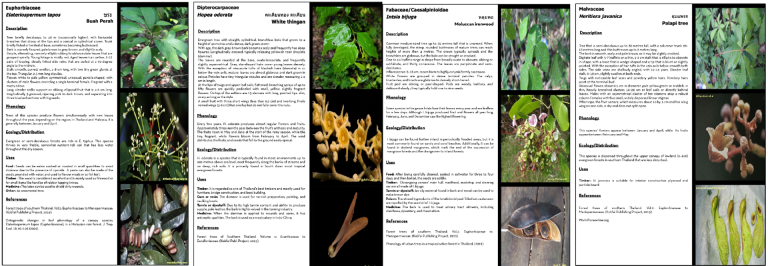

The second planting event took place in November 2024. Between October 2023 and November 2024, our seed collection activities increased in frequency and our nursery infrastructure expanded. We were therefore able to acquire a total of 22 new species and 144 new trees (Table 4). Work is ongoing to develop Species ID sheets for each species used in our reforestation project to help with educational programs and knowledge dissemination (Fig 6).

Planting events were planned and the site to be planted was prepared prior to the event. Selected trees were labelled, and bamboo sticks were placed at the planting location. Randomization was used to distribute trees randomly with a second rule of distribution accounting for the avoidance of two large trees next to each other. A map was created indicating the location of each tree to help with subsequent monitoring efforts.

3.1.3. Monitoring

3.1.3.1. Biodiversity monitoring

i. Plants and landscape physiognomy

We monitored landscape physiognomy using sample-based vegetation surveys at the circular sample plots established during the rapid site assessment. Three surveys were conducted in Dec. 2023, Apr. 2024 and Dec. 2024 (Fig. 7)

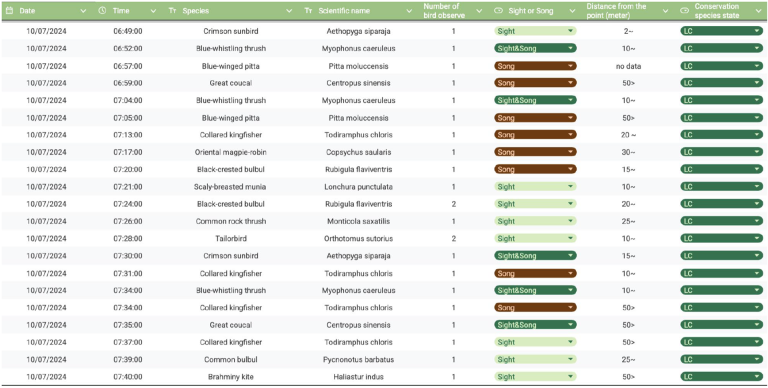

ii. Bird abundance

Bird species were observed during initial transect walks, including typical limestone karst species such as the Common rock thrush (Monticola saxatilis), the blue whistling thrush (Myophonus caeruleus) and the Eastern barn owl (Tyto javanica) and numerous disturbed forest or edge species such as common tailorbird (Orthotomus sutorius), the greater coucal (Centropus sinensis), the oriental magpie robin (Copsychus saularis) and the Streak-eared bulbul (Pycnonotus conradi). Presence of more sylvatic species such as the Black-crested bulbul (Rubigula flaviventris) and the Lineated barbet (Psilopogon lineatus) is encouraging but too rare as yet (Fig. 8).

3.1.3.2. Tree performance and other indicators of restoration success

Baseline monitoring was conducted in October 2023 as well as monitoring for tree performance in December 2024 and March 2025 (Fig. 9). As of March 2025, 85% of the trees planted in October 2023 were still alive and most remained healthy and growing. Periods of intense growth were observed during the rainy season. While none of the 315 trees have produced flowers or fruits yet, many have suffered from herbivory by long-tailed macaques, requiring frequent checks and maintenance

3.2. Community Mobilization & Events

3.2.1. Local team formation and project ownership

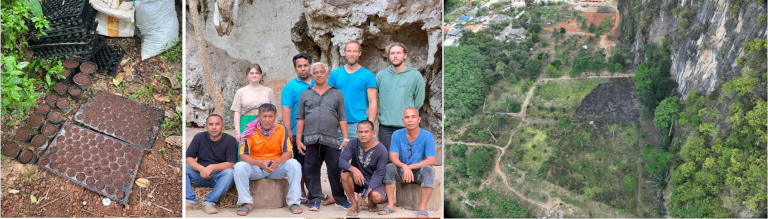

The project is owned by both NatureMind-ED core team and key local community champions (Fig. 10). The core team involves land owners as well as local government representatives, NatureMind-ED project coordinators and project leader as well as interns supporting the project for a certain period of time.

Figure 10. Core local community project team and NatureMind-ED representatives. From left to right, Mr.Worawut Daengnui (Coordinator), Miss Emilie Nakache (Student, NMED), Mr.Pramote Changrue (District administration, Aonang and Land owner), Mr.Anudit Kongyi (project coordinator NMED), Mr.Ampond Daengnui (Land owner/informal leader), Dr. Pierre Echaubard (Project leader, founder NMED), Mr. Wichan Anupak (project coordinator NMED), Mr Lubin Herve (Student, NMED), Mr.Sawad Mheenui (District administration, Aonang, Land owner)

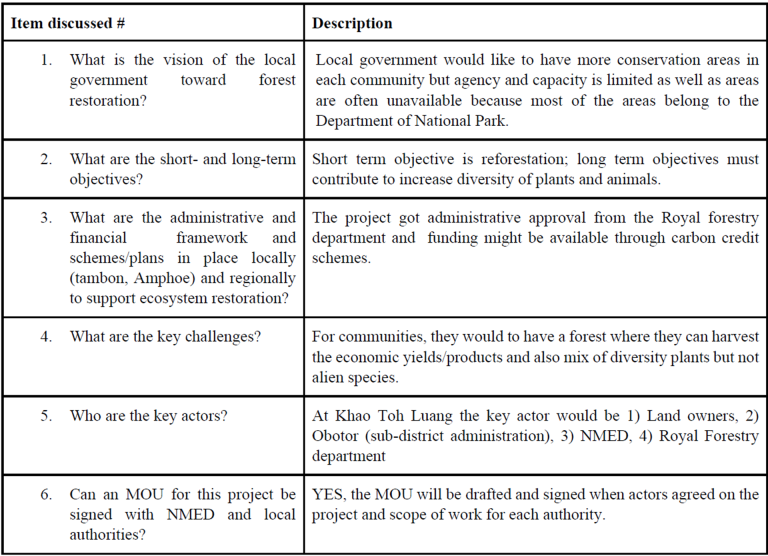

An inception meeting was held in June 2023 to agree on the project’s direction and objectives (Table 5). Through subsequent monthly meetings and a dedicated participatory mapping session, the team navigated land tenure issues and secured an informal agreement from landowners to allocate a portion of their land adjacent to the mountain for reforestation (Fig 11).

3.2.2. Community events

At the time of writing, 3 community planting events have been organized, held in October 2023 (approx. 40 participants, mostly local community members and schools), November 2024 (approx. 60 participants mostly local community members and schools) and June 2025 (125 participants, larger group of community members, schools, national park representatives, local administration offices, private sector). The events served as critical gathering symbol of community collective action and centering around a common goal. These events were used as a sort of general assembly during which we shared updates about the project to the wider stakeholder community, we build awareness through educational activities, raise funds and increase the project visibility as well as reputation (Fig 12 and Video).

3.2.3. Trail development

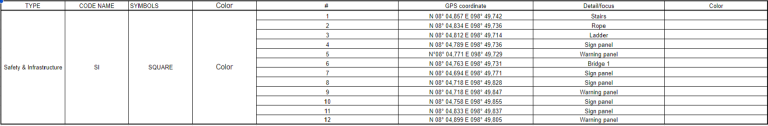

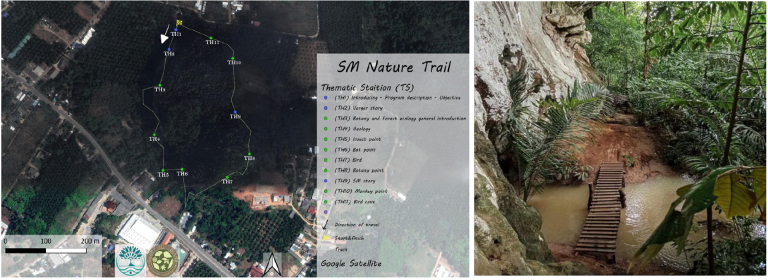

A key project output is a forest nature trail developed through community consultation to provide educational access to the reforestation area and revive local ecological knowledge. The development process included reconnaissance hikes that identified 11 thematic stations and 12 infrastructure points for the trail, which also involved creating maps and informational signs (Fig 13).

3.3. Youth education

Naturemind-ED delivered 14 weeks of experiential education to local school children, with sessions held every Friday afternoon at Kao Tho Luang, near the reforestation area. Age group hosted varied between P1-P4 (primary school (Prathom Suksa), lasting 6 years (Grades 1-6)), P5-M1 (lower secondary school (Matthayom Suksa), (Grades 7-9), M2-M4 (upper secondary school (Matthayom Suksa), (Grades 10-12) (Fig. 14).

3. CHALLENGES

The restoration project around Khao Toh Luang has faced substantial barriers, notably due to existing tax policies. Current regulations impose higher taxes on land deemed “overgrown,” incentivizing landowners to regularly clear-cut or engage in monoculture planting rather than allow natural regeneration. Furthermore, financial, capacity, and access limitations make formal restoration challenging.

Engaging local landowners also proved difficult initially, as many harbored reservations about collaborating with organizations involving foreign partners. Trust-building required extensive formal and informal dialogues spanning several months. Naturemind-ED addressed these concerns through discussions emphasizing tangible and intangible benefits of reforestation, including cultural ecosystem services, traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), nature-based business model developments, and the revival of locally significant species such as the Luk Chok palm. Highlighting flood protection and climate resilience also resonated, as intact forests around Krabi notably suffer less severe flooding compared to neighboring areas.

Eventually, a core group of four landowners actively engaged after extensive one-on-one interactions and listening sessions, even overcoming language and familial complexities. One landowner opted for leasing arrangements to retain control while enabling restoration. Institutional challenges emerged when attempts to formally designate the area as a Community Forest encountered bureaucratic hurdles, leading to reliance on informal collaborations supported by local government officers.

Ecologically, the availability of seedlings dictated restoration choices, highlighting the need for robust seed banks and ongoing phenology research. Additionally, concerns about increased human-wildlife conflict, particularly monkey damage to crops, have emerged. One local family, operating a nearby durian farm, remains hesitant until effective mitigation measures against wildlife intrusion can be assured.

Constant stakeholder engagement, including addressing individual concerns like those of a hesitant older landowner, underscores the necessity of regular “reality checks.” Such interactions ensure project alignment with local needs and help manage stakeholder frustration.

Long-term challenges persist, particularly regarding sustained community buy-in and consistent monitoring. Outcomes from restoration activities, such as flood risk mitigation and biodiversity conservation, only become visible over extended periods. Thus, short-term incentives provided by Naturemind-ED’s social-enterprise model have proven essential in maintaining engagement and support. Incremental successes, like the establishment of a parkour playground, further illustrate the effectiveness of a community-driven approach in reconciling ecological, economic, and social objectives.

4.Lessons learned and the way forward

Trust, shared ownership, and adaptive project management have enabled the emergence of a locally governed forest that symbolizes reconnection with nature and community sovereignty over natural resources. By rejecting “community forest” status, landowners signal confidence in managing restoration autonomously—underscoring the value of informal mechanisms like Other Effective Conservation Measures (OECMs) in achieving biodiversity and climate goals with less bureaucracy and greater local innovation.

Although still early in its development, the project demonstrates how a blend of genuine community engagement, contextualized ecological knowledge, a social-enterprise model, and transformative education can scale forest restoration. The site has become a living hub for collaboration and learning. While a robust monitoring framework is still needed, early results affirm the promise of regenerative, community-driven approaches to ecosystem restoration.

5. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful for technical guidance provided by the Forest Restoration Unit of Chiang Mai University. Funding has been provided by NatureMind-ED through its community-based ecosystem restoration internal funding scheme. Additional funding was received by Anana Ecological resort as part of an ecological sponsorship program. The authors are grateful for the ongoing support of GVI and RealStep through the ecosystem restoration internship program jointly implemented with NatureMind-ED. We feel honored and grateful for the people of Krabi who allow us to lead local natural resource management affairs on their land.

6. BIBLIOGRAPHY

T.M. Basuki, P.E. van Laake, A.K. Skidmore, Y.A. Hussin, 2009. Allometric equations for estimating the above-ground biomass in tropical lowland Dipterocarp forests, Forest Ecology and Management, Volume 257, Issue 8,

Bhagwat T, Hess A, Horning N, Khaing T, Thein ZM, Aung KM, et al. (2017) Losing a jewel—Rapid declines in Myanmar’s intact forests from 2002-2014. PLoS ONE 12(5): e0176364. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176364

Curtis and Gough 2018 Forest aging, disturbance and the carbon cycle. New Phytologist, Volume 219, Issue 4 p. 1188-1193

Elliott, S. D., D. BlakESlEy anD k. HarDwick, 2013. Restoring Tropical Forests: a practical guide. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; 344 pp.

Elliott S, Tucker NIJ, Shannon DP, Tiansawat P. 2022 The framework species method: harnessing natural regeneration to restore tropical forest ecosystems. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378:https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.007

FAO. 2020. Agriculture and climate change – Law and governance in support of climate smart agriculture and international climate change goals. FAO Legislative Studies No. 115. Rome.

Gann et al. 2019 International principles and standards for the practice of ecological restoration. Second edition. Restoration Ecology Vol. 27, No. S1, pp. S1–S46

Goosem, S., & Tucker, N. I. J., 1995. Repairing the Rainforest. Cairns: Wet Tropics Management Authority. 71pp

Deborah Lawrence and Karen Vandecar, 2015. Effects of tropical deforestation on climate and agriculture. Nature Climate Change 5, 27–36; 2015

L Lebel, S Chantavanich, W Sittitrai, 2017. Floods and migrants: Synthesis and implications for policy. Living with Floods in a Mobile Southeast Asia, 188-197

Jean-Philippe Leblond, 2019. Revisiting forest transition explanations: The role of “push” factors and adaptation strategies in forest expansion in northern Phetchabun, Thailand, Land Use Policy, Volume 83, Pages 195-214,

Martin, A. R., & Thomas, S. C. (2011). A reassessment of carbon content in tropical trees. PLoS ONE, 6(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0023533

Jim Penman, Michael Gytarsky, Taka Hiraishi, William Irving, and Thelma Krug 2006 IPCC GUIDELINES FOR NATIONAL GREENHOUSE GAS INVENTORIES

KHWANKHAO SINHASENI 2008 NATURAL ESTABLISHMENT OF TREE SEEDLING IN FOREST RESTORATION TRIALS AT BAN MAE SA MAI, CHIANG MAI PROVINCE, Thesis for Master of Science, Chiang Mai University